The street as a character in the narrative of a city: the case of Vasilissis Sofias Avenue

Andriopoulos Themis

Culture, History, Quartiers

2019 | Jan

The street as a protagonist in the city narrative

In the context of Greek literature there are hundreds of references to the city of Athens as the setting in which the city’s narrative unfolds. Moreover in recent years, the references to a multifarious and largely equal participation of a city as an independent «agent of action» in the main characters of it’s own narrative are increased.

At the same time the city itself could be read as a novel where the narrator is not merely a «real person» or an omniscient storyteller but the streets of a city. This happens because the narrative of a city composes the plot and combines aspects of its ideology in the same way that the characters convey the ideological stances of a novel, giving their own «battle» to prevail through the dominance of the story itself (Δοξιάδης, 1988). In this way we could talk about a street as a character in a narrative about a city.

There are suspicious and dark streets, odorous streets, spectacular and noisy streets, festive and commercial streets, escaping streets, streets for meetings and for walks. In those streets, there are compressed changes and fluctuations between public and private, space and time as well as, the ephemeral and transitional normality that highlight diversity. There, accidental happenings take place, serendipitous or ordinary events. In the narrative of a city the street is not only the storyteller but also the main field of urban experience. In the street, practices of space go beyond the visible horizon and beyond the networks of interactions that escape attention. At the same time it traces a «dark and blind mobility of the inhabited city» (Μισέλ ντε Σερτώ, 2010: 247) through a fabulous experience of space. The street announces: what will happen, what has happened and what is now taking place.

In this great and ambitious novel of a city every street could unfold different aspects and incidents however not all the streets could be the protagonists in the same way. This condition takes place because, in the labyrinth of urban post-modern experience, the streets do not only «exist» but they «act» as the agents of action. In other words, we can claim that the street plays the same role as the main character of a narrative. That way, both the character and the street become subjects who function as agents and the conjunction factors of the plot and the city itself.

We have deliberately chosen to talk about Vasilissis Sofias Avenue (hereafter called V. Sofias Ave.) in order to reveal that the narrative of Athens city can be read in such a way that the action of the streets as characters can emerge as the most fundamental and determining factors of urban experience and as agent of giving meaning by changing identities. In this context the streets constitute continuous production matrices of urban identities. The characters of a story are carriers of different actions; likewise, the streets can retell the footprints of the urban experience in different ways. No street speaks the same language.

Starting from the fundamental rhetorical schemes of narration (the metaphor and the metonymy), we consider the commonly accepted attribution of V. Sofias Ave. as a central artery of the city to be a fundamental metaphor. This metaphor demonstrates a vital conceptual definition for the identity of Athens (Τουρνικιώτης, 2000) (Photo 1). It is known that the artery is a large vessel that transfers blood from the heart to the other vital organs of man; but isn’t the city a living organism whose life is determined by its arteries?

Photo 1: Sofias Avenue a central artery of the city. Taken from the Hilton Hotel towards the Ambelokipoi neighbourghood

In order for it to be a metaphor it must also be a metonymy (Δοξιάδης, 2008). Thus, V. Sofias Ave. is a fundamental metonymy of Athens. This connection stands not only because metonymy is a cognitive process in which a concept provides logical access to another concept (Βελούδης, 2005), nor because it relates the part to the whole but also because its landmarks compose multiple parts in the syntagmatic chain of the narrative about the city. Therefore, as man means «speech» and scorpion means poison in the same way, V. Sofias Ave. means Athens.

The spatio-temporal trilogy of Vasilissis Sofias Avenue

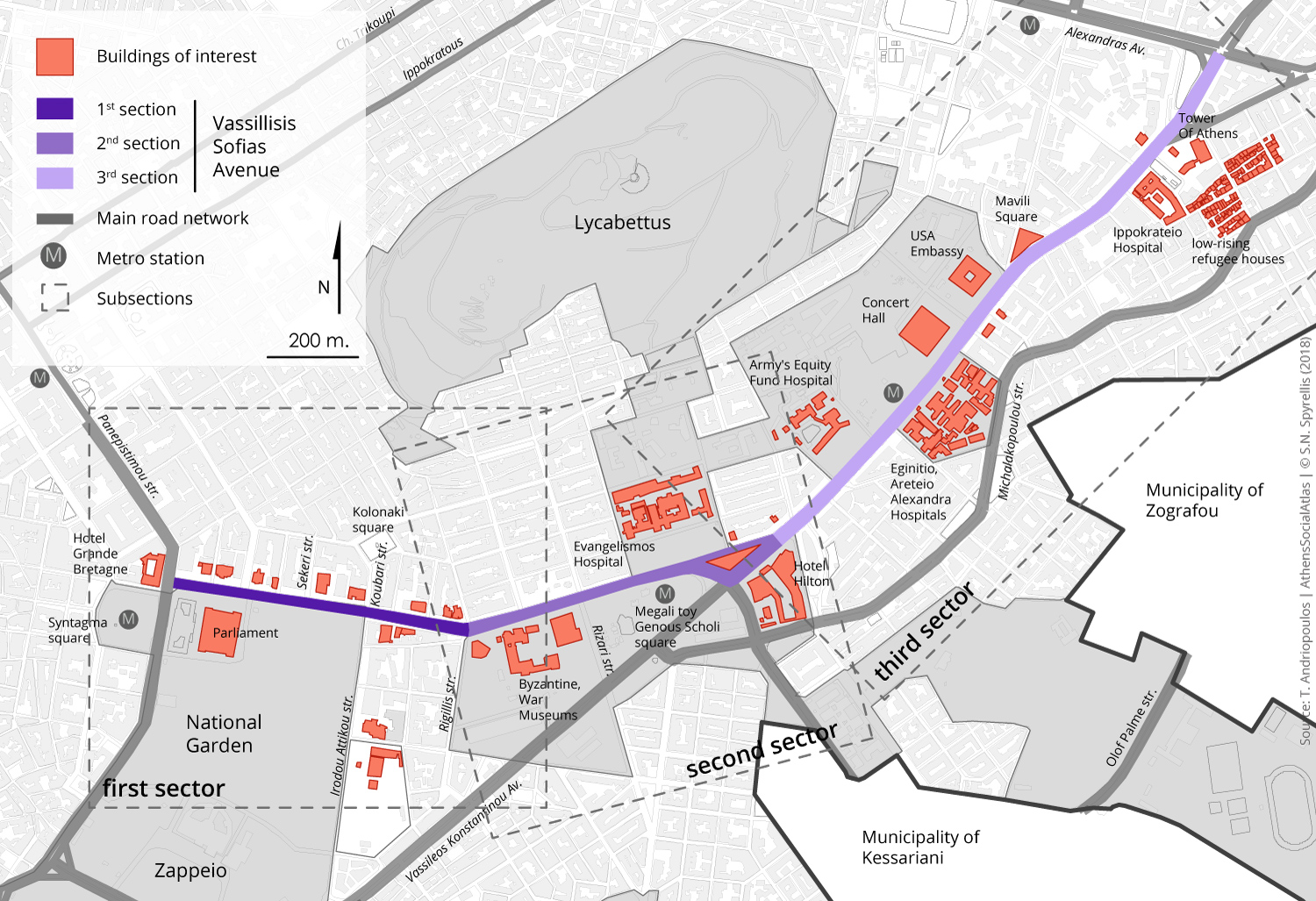

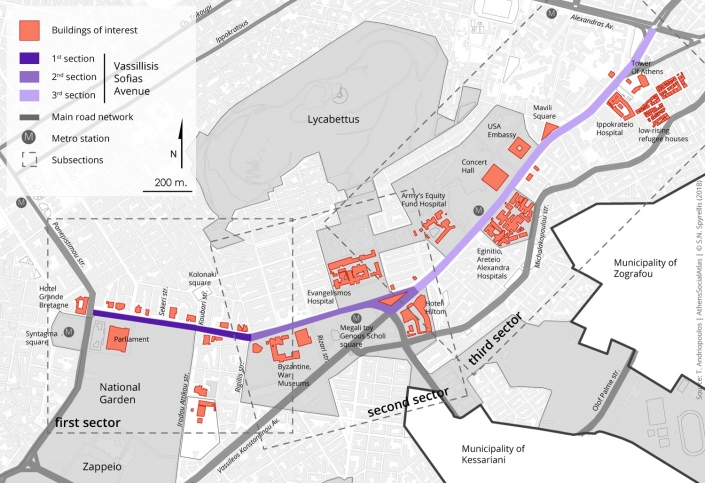

Tracing V. Sofias Ave., we can discern that its two large «curves» divide it informally into three «natural» sections, making the turns of the street look at the same time as turning points in time.

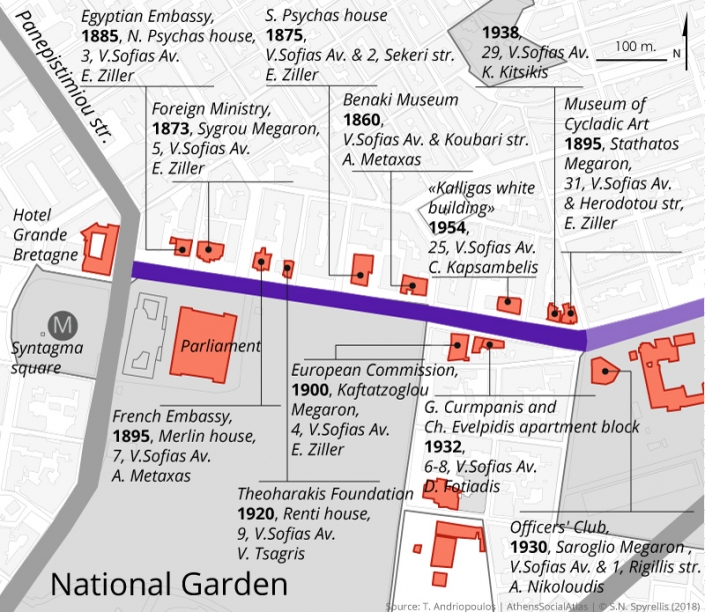

Map 1 : Vasilissis Sofias Avenue

Following the avenue from Syntagma Square towards Ambelokipi, the first and most imposing section includes a large area from the building of the Greek Parliament, the old Palace, to Herodotus Str and Rigillis Str. Within that section one can see the National Garden, almost all the remaining neoclassical buildings [1], glorious and imposing houses of the wealthiest social strata of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as well as luxurious post-war residences designed by famous architects. All that makes V. Sofias Ave. the most elegant boulevard and at the same time a place / symbol of urban prosperity, continuing until today to be a landmark of Athens.

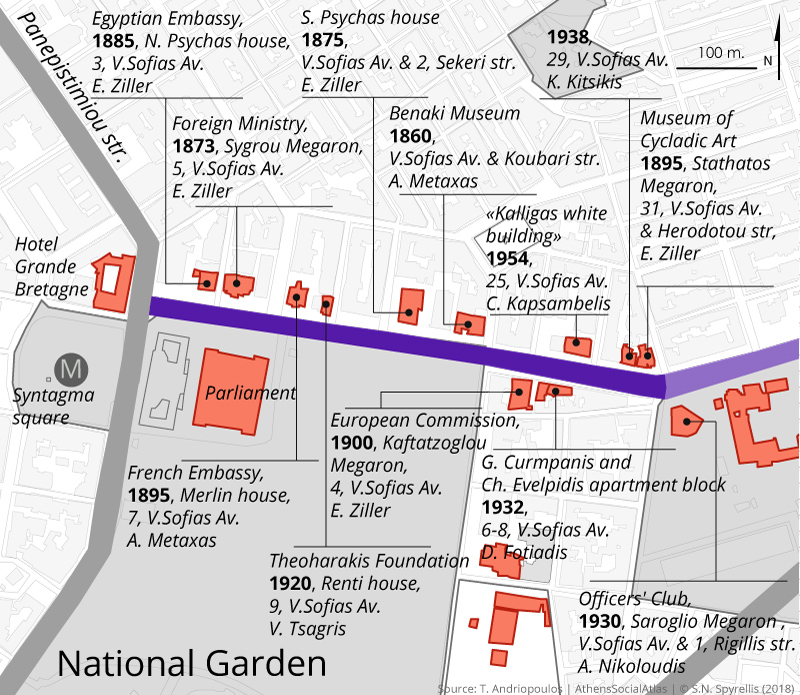

We can mention in particular Nikolaos Psychas’ house (1885, 3 V. Sofias Ave. , E. Ziller [2], which now houses the Egyptian Embassy, the Kaftatzoglou’s Mansion (1900, 4 V. Sofias Ave., E.Ziller), which today accommodates the European Commission headquarters , Andreas Sygros’ Megaron (1873, 5 V. Sofias Ave., E.Ziller), which houses the Foreign Ministry, the Merlins’ House (1895, 7 V. Sofias Ave. , Anastasios Metaxas), which hosts the French Embassy, the apartment block of G. Curmpanis and Ch. Evelpidis (1932, 6-8 V. Sofias Ave., Dimitris Fotiadis), the house Renti (1920, 9 V. Sofias Ave., Vassilis Tsagris) which today hosts Theocharakis Foundation Stefanos Psychas’ house (1875, V. Sofias Ave. and 2 Shekeris Str, E. Ziller), Harokopou or Emmanuel Benakis’ house (1860, V. Sofias Ave. and 1 Koumbari Str, A. Metaxas), where the homonymous museum is placed today , the “white house Kalliga” (1954, 25 V. Sofias Ave., Constantinos Kapsambelis), a luxurious apartment block of the Interwar period by K. Kitsikis, which combines classic elements with modernism (1938, 29 V. Sofias Ave.). The first section of the road ends at Stathatos’ Megaron on the right (1895, 31 V. Sofias Ave. , E. Ziller), where the Museum of Cycladic Art is based and, right across the street, on the left, Saroglio Mansion, where the Military Officer’s Club is based (1930, V. Sofias Ave. and 1 Rigillis Str, Al. Nikolaoudis) [3]. (φωτ. 2-14).

Map 2: The first section of Vasilissis Sofias Avenue

Photos 1-12:

The second section of the street starts at the Ilisia House (1848, 22 V. Sofias Ave. , Stamatis Kleanthis) where the Byzantine Museum is now located, goes past the War Museum (1975, Rizari, Thucydides Valentis) and the Evangelismos Hospital, it ends up on two important landmarks. The first one is a sculpture named Dromeas (Runner) by Kostas Varotsos, which is situated in the the Phanari Greek Orthodox College square. The second landmark, Hilton Hotel, is located opposite the «red apartment block» (1927, 55 V. Sofias Ave., Konstantinos Kitsikis). It is one of the most representative buildings of modernity, not only a symbol of social prosperity but also a symbol of the involvement of Greece in the international tourism network. (Τουρνικίωτης, 2000).

The Hilton was built in 1963 based on designs by Emm. Vourekas, Pr. Vassiliadis and S. Staikos. Moralis’ embossed brushstrokes are above the main entrance, as the famous painter was looking for “Greekness” in response to the imposing size of a global force which then was at the height of its power. (Φιλιππίδης, 2000) (Photos: 15-18 ).

Map 3: The second section of Vasilissis Sofias Avenue

Photos 13-16:

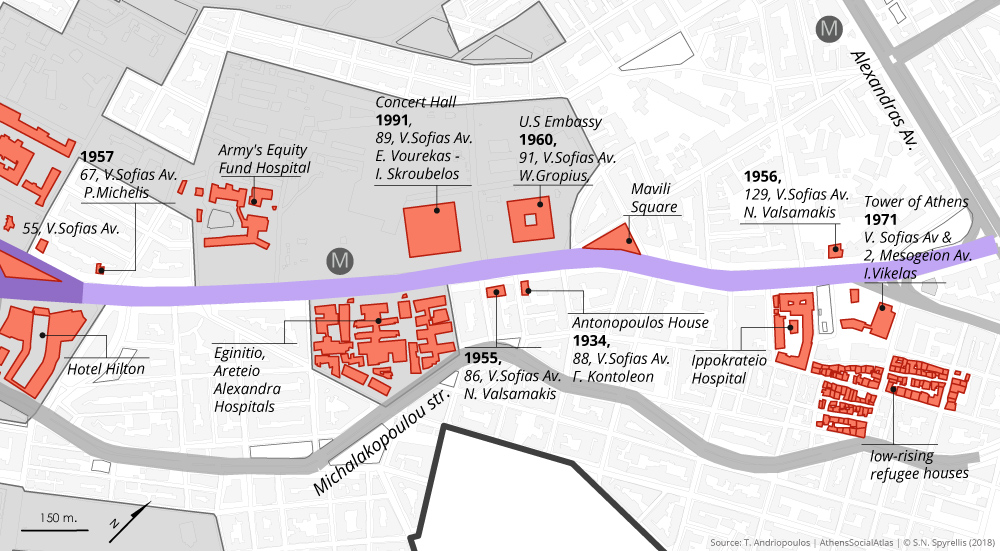

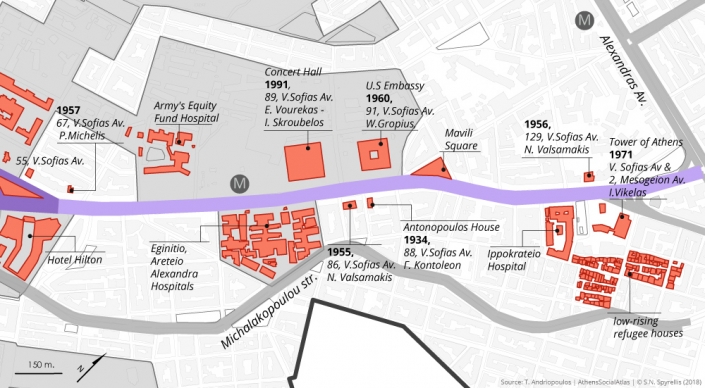

The third section of the street starts just after the Athens Hilton Hotel and is clearly dominated by modernist aesthetics. That is, the part of the street starting from the Army’s Equity Fund Hospital and along the four other Hospitals named Eginitio, Aretaeio, Alexandra and Ippokrateio is adorned with post-war apartment blocks and buildings by famous architects like Nikos Valsamakis and Panagiotis Michelis (Photos: 19-26). There is the exception of Antonopoulos’ residence (1934, 88, V. Sofias Ave., George Kontoleon) with the architect’s innovative idea that the façade faces towards the Acropolis rather than towards the street (Photos:19-26).

In this section we can see the Concert Hall (1991, 89, V. Sofias Ave., Vourekas-Skroubelos) and the U.S Embassy (1960, 91 V. Sofias Ave.). The latter is designed by the famous architect Walter Gropius and is one of the most well-known architectural artworks and powerful landmarks of Athens (Photos: 27-28). The only entertainment venue of V.Sofias Ave. is in this section and not by accident. It is Mavili Square with various restaurants, bars, cafes and pastry shops with the most famous one being Lora’s bar, which has been there for almost four decades, since 1967 (Photos: 29-30). The most modern part of the street has been completed in a clearly symbolic way at the Towers Of Athens (1971, V. Sofias Ave. and 2 Mesogeion Ave., J. Vikelas), in the first attempt to build a skyscraper in Greece (Photos: 31-32).

Map 4: The third section of Vasilissis Sofias Avenue

The only entertainment venue of V.Sofias Ave. is in this section and not by accident. It is Mavili Square with various restaurants, bars, cafes and pastry shops with the most famous one being Loras’ bar, which has been at the top for almost four decades since 1967 (Photos: 29-30).

The most modern part of the street has been completed in a clearly symbolic way at the Towers Of Athens (1971, V. Sofias Ave. and 2 Mesogeion Ave., J.Vikelas), in the first attempt to build a skyscraper in Greece (Photos 31-32).

Thus, V.Sofias Avenue appears to resemble a fantastic architectural biennale which displays architectural artworks of more than one century. These architectural artworks, within a spatio-temporal linearity, have defined and put together not only the visual identity of the urban structure of Athens, but at the same time its individual and equally important ideological identities, the extent and the reputation of which inevitably and imperatively outweigh it.

Εικόνες 19-32:

The rhetoric of power from the city’s principal narrator

According to the above description we can ascertain that V. Sofias Ave. composes extremely important aspects of the Athenian urban identity through the realm of the buildings facades. Perhaps those aspects which have defined this identity as an archetype.

In addition this dominance of the signifiers, V. Sofias Ave. is also a set of places that could be called “prominent”. A special type of a «prominent» place is the «exemplary» place. These are unique places, that hold a prominent place in social memory, hypostatize the collective historical experience and construct common conceptual intakes (Τζανάκης-Σαβάκης, 2003). The exemplary places are distinct monuments that we must remember (Τζανάκης-Σαβάκης, 2003:89).

A characteristic example of an exemplary place is the first part of V.Sofias Ave. However, this does not mean that some of the various landmarks mentioned, such as the American Embassy and the two Towers of Athens, do not contribute to the collective urban experience.

The ideological aspect of V. Sofias Ave., at least until Stathatos Megaron and the Officers’ Club, is completely evident.

The desire of urban collective consciousness for Athens to be as it used to be in the early 20th century and the common «disappointment» for an Athens lost in «apartment buildings and cement» is largely based of those emblematic fragments of the past at the beginning of the road. Behind this idea there is an underlying ideologization of nostalgia which ignores the specific social conditions of Greek society from the beginning of the 20th century onwards (Φιλιππίδης, 2000).

Probably this sort of nostalgia implies a longing for and a quest for purity and authenticity of the form that is easily readable and recognizable as opposite to embarrassment in the face of diffuse metropolitan fragmentation. In this sense, however, nostalgia indicates a mood for the consumption of the past my means of forms conforming to the rhetoric of purity.

seems to be united to a single “person” as the “hero-narrator-author” (Genette, 2007: 325). This street is a “named” character who writes the history of the city playing the leading role in every scene; at the same time, it narrates with accumulated historical tension and arrogance in a pompous and self-referential way the city’s history which is no less than the history of the city centre itself [4]. Within a system of rhetorical forms there will be shaped the richest repertoire of emblematic representations. Rightfully, the street starts from the Great Britain Hotel which is an imposing landmark of Athens’ history and it ends up at the intersection of V. Sofias Ave., Alexandras Ave. and Kifissias Ave. (Photos: 33-34).

Photos 33-34:

In the work entitled «Discourse Analysis: Α Socio-philosophical Grounding» by Kyrkos Doxiadis, one of the four interconnected axes proposed for a discourse analysis is the axis of concepts which refers to the interrelationship of different sorts of discourse within the narrative and the concepts that come out of that process [5].

In particular, referring to the axes, the author exemplifies the concept of temporality which fits perfectly with the case of V.Sofias Ave. as a character in the narrative of the city. He points out: “I am referring mainly to cases where the characters themselves narrate incidents that have already occurred, so that this narration constitutes an important part of the plot itself” (Δοξιάδης, 2008: 176). The question raised here is whether V.Sofias Ave. unfolds the incidents that make up a significant part in the narrative of the city to such an extent that the street itself makes any subjects which move within it to disappear since it overcomes the subjective performances in the name of its complete hypostatisation as a self-contained entity.

For one thinks that, in this street of continuous flow, there is no room for humans that there are no subjects but only landmarks and transient meeting points.

This realization reminds one of the image of Athens as it appears in the «Violet Town» by Angelos Terzakis. It is remarkable indeed that the writer, in his effort to describe the chaotic shape that the city had been taking even before the Second World War, will use the word “artery”. [6].

If a main feature of the stroller (flâneur) is his/her ability to be lost in the city, it is impossible for him/her to have a feeling of subjectivity when walking along V. Sofias Ave. (Σταυρίδης, 2007).

Insofar as the stroller is not willing to familiarize himself with the city and constantly tries to “rewrite” the urban meaning by composing its elements in order to rearrange them in a montage process that becomes impossible. All the more, when the stroller’s wandering takes place in V.Sofias Ave., the road of absolute familiarity and established performances but without thresholds.

In this street there is not discontinuity that could reverse the meaning of the city, no arcades that could become a place of transition out of routine and boredom or passages to the unfamiliar and to the otherness (Σταυρίδης, 1999). In V.Sofias Ave. you cannot get lost, you cannot condemn any part of it to obscurity or inertia in order to compose other “unwitting spatial reversals” [7] (Μισέλ ντε Σερτώ, 2010: 256). If we defined walking as a “speech space” (Michel de Sarto, 2010), the rhetoric of walking would remain not just absent but speechless. Even if the subjects are willing to glance at the unfamiliarity and the finding thresholds the street deters a random wandering that will give a different meaning to the boundaries and the subjects who go to past them. These are associated with the following metonymic connection: a threshold is the spatial metonymy of a discontinuity. However at the end of V. Sofias Ave. there is a single threshold, a discontinuity that actually breaks through place and time.

That is just behind the two skyscrapers there are still some fragments of the more recent past of V. Sofias Ave. In this area we can see a few crumbling low-ceiling refugee houses from the Interwar period as well as the remains from other abandoned ones, remarkable of a neighborhood with no scent of the metropolitan awe of the two imposing buildings located just a hundred meters away.

Crossing the threshold between the two multi-storey buildings one finds himself transferred from extravaganza of the avenue to a past time and place that reminds of forgotten districts of other times (Photos 35-39).

Photos 35-39:

Since ideology “is a way of exercising power in discourse and through discourse” (Δοξιάδης, 1988: 37), the power that is wielded by the speech of V. Sofias Ave. as a character over the discourse of the city is distinct and is achieved through an ideological “battle of discourses” for ideological-prevalence.V. Sofias Ave., being the dominant and central subject of the city, articulates a disarming discourse by establishing not only a local regime of truth [8] but also an hypertopic one. The ideological identity of the landmarks that construct the discourse of V. Sofias Ave., particularly in its first and second parts, overcomes the locality of the street and its boundaries. Due to this condition V. Sofias Ave. is not a strictly defined street but the space whοse limits are up to the extent of the intensity of its ideology. In other words is a stylistic territory [9].

For example, the surroundings covering Kolonaki, Rigillis, Vasileos Konstantinou and Herodes Atticus streets, which are residential areas of the upper class as well as the location of the most institutionalized symbols of political power: the Prime Minister’s dwelling (the Maximos Residence) and the Presidential Palace (the New Royal Palace).

V.Sofias Str is one of the most characteristic examples of the relationship between ideology and power in the field of urban discourse, as well as of the power of the street in its metonymic connection with the city in its narrative process. The street as a “capacitor2 and a mirror of an order is “pure” from venues of “disorder” and other “exceptional” situations (Σταυρίδης: 2010). It has no homeless, no immigration points, no abandoned and occupied buildings, as roads such as Panepistimiou Ave. the physical extension of V. Sofias Ave. or the next legendary extension Patision Str., do have. It is not by coincidence that the only cinema located at the end of V. Sofias Ave. has become the point of a “compulsory meeting” (Μεταξάς, 1997: 180) There are two metro stations, the Concert Hall station and the Evangelismos Hospital station, that could be described as “social interaction places” and which have distinctive intensity. However, this tension is mainly channeled under the ground. Thus it seems that this street does not accept the intensity of the crowd therefore it repels it inside its buildings for the sake of preserving its image, which should remain brilliant and sheltered at all costs

If the postmodern condition requires the rescue of thοse issues that are non-represented in Reason, the “linguistic game” about V. Sofias Ave. must be visible and easy to understand to such an extent that it ceases to be a ”game” anymore, remaining that way subjugated to Reason. This is the concept behind the street’s modern style. Here, instead of uncertainty, there is plenty of regularity, another concept about the road that supports its hegemonic state.V. Sofias Ave. is not simply a limited street but a set of places that constitutes an autonomous, dynamic, ideological outline with its own powerful structure and language. According to the Aristotelian classification, this street has got a “genos” (genus) but without being an “eidos” (species). In this way, it is classified in a dissimilarity order, because the difference in a metonymy is given by definition. Regarding the narrative status, the authority of V. Sofias Ave. does not stem from an omniscience but emerges from the paradox that it is constituted by the fundamental metonymy above mentioned. This paradox consist of the fact that when V. Sofias Ave. is getting autobiographical, namely it “talks” about itself, the focus is on Athens. However, when it tries to talk about Athens the focus is on itself. Thus, the paradox is exhausted by the fact that while V. Sofias is a “sui generis” street it is simultaneously inhospitable to otherness

Concluding, as regards the aesthetization of V. Sofias as a symbol of national purism there is eventually no doubt about the form of the stylistic tension which is conveyed via purity. This tension refers to the ideological strength at the oldest part of the street which starts at the Palace and the other neoclassical houses whereas at the newest end of the street where the two towers are located it is associated with the ideology of “straight-line”. This ideology of the “straight-line” is a metaphor which implies the “determination of the political power to act steadily and straight” for it is not by accident the time chosen for the construction of the two skyscrapers (Μεταξάς, 2003: 113) (Photo 40). The repertoire of V. Sofias consist of a materialist rhetoric represented in both the neoclassical architecture standing out on buildings of political power and in a series of modern public buildings with glass facades which provide an illusion of transparency by letting the eye see through the glass (Μεταξάς, 1997) (Photos 41-42).

The merit of this rhetoric when it is not exhausted in repeated standardized incidents and representations of the past it is constituted by exemplary landmarks with a clear social imprint.

The stylistic territory at the crossroads of V. Sofias with Irodou Attikou Str have been quite vividly illustrated in the last scene of the famous film “The Forged Sovereign” by George Tzavellas. In this scene it is indicated that the urban experience is not an individual matter but involves subjectivities and competitive social relationships.

However, if the street’s metonymies belong to the city, its metaphors always belong to the reader.

Photos 40-42:

[1] According to Andreas Giakoumatos (Γιακουμακάτος 2004: 13), the term “neo-classicism” is wrong because it corresponds neither ideologically nor in time to the movement of European neo-classicism that is completely worn out from the European revolutions of 1848.

[2]The first date in brackets refers to the year of the completion of construction, then, there is the address of the building and finally the name of the architect in case it is not mentioned in the text.

[3] George Sariyannis’ (Σαριγιάννης 2005) notes referring to the period between 1930s and 1940s when 625 new apartment blocks were built in the center of Athens, the buyers of which belonged to the upper class, as were the architects who designed the blocks. A typical example is the case of Konstantinos Kitsikis. See also Christos Iacovidis (Ιακωβίδης 1982: 48-74)

[4] According to Uri Margolin (2009: 61-79) the character in a narrative can be appeared either with a particular name, a description or a personal pronoun.

[5] The other three are: the axis of objects referring to the relationship of discourse with other elements beyond discourse, the axis of the way of speaking in relation to ways that the subject interferes in the narrative and the axis of thematic exploring discourse with authority. See also Kyrkos Doxiadis (Δοξιάδης 2008: 179-188).

[6] “It looks like a snake, which has fallen asleep between three mountains, with its neck leaning downwards down to the sea, and its scales playing with sunlight. He is lost and he is looking at the city. When did this inexplicable happen? For years now, living in the same city, he is also circulating in its blood, the violet and juvenile which animates the city’s arteries. He goes, he comes, he works, he rejoices and hurts but you could say that he does not feel anything from his surroundings” (Τερζάκης, 2006: 54).

[7] It is not by accident that even on the anniversary of Athens Polytechnic uprising in November 1973, the negative symbolism of the US Embassy moves at about the same levels of intensity, imprinting and tension as the symbol of the anniversary. The spatial dimension is evident, as it is characteristic that the news on that day is presented not when the march started but when it is reached at the US Embassy in V.Sofias Ave.

[8] See Louis Althusser (1983: 115).

[9] The term “stylistic territory” is inspired by the concept of the “functional territory” proposed by Kyrkos Doxiades (Δοξιάδης 1995: 39) who defines it as the area in which its limits are functional and not factual and is extended to the point where people operate as liberal and rational subjects.

Entry citation

Andriopoulos, T. (2019) The street as a character in the narrative of a city: the case of Vasilissis Sofias Avenue, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/vasilissis-sofias-avenue/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.86

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

References

- Αλτουσέρ Λουί (1983), Θέσεις, Αθήνα:Θεμέλιο

- Βελούδης Γιάννης (2005), Η σημασία πριν, κατά και μετά τη γλώσσα,Αθήνα

- Γιακουμακάτος Ανδρέας (2004), Ιστορία της Ελληνικής αρχιτεκτονικής 20ος αιώνας, Αθήνα:Νεφέλη

- Δοξιάδης Κύρκος(1988), «Foucault, Ιδεολογία, Επικοινωνία», Επιθεώρηση Κοινωνικών Ερευνών, τχ.71, σσ: 18-43

- Δοξιάδης Κύρκος (1995),Εθνικισμός, Ιδεολογία, Μέσα Μαζικής Επικοινωνίας, Αθήνα:Πλέθρον

- Δοξιάδης Κύρκος(2008),Ανάλυση Λόγου.Κοινωνικό-φιλοσοφική θεμελίωση, Αθήνα: Πλέθρον

- Genette Gerard (2007), Σχήματα ΙΙΙ, Αθήνα:Πατάκης

- Ιακωβίδης Χρίστος (1982), Νεοελληνική αρχιτεκτονική και αστική ιδεολογία ,Αθήνα: Δωδώνη

- Τζανάκης Μανώλης–Σαββάκης Μάνος(2003), «Οι τόποι ως ιστορικοπολιτισμικά αντιπαραδείγματα και ως σύμβολα κοινωνικών ορίων:Σπιναλόγκα και Λέρος»,Το Βήμα των Κοινωνικών Επιστημών, τομ.Ι, τχ.36, σσ:87-126

- Margolin Uri(2009), «Character». In David Herman (ed.),The Cambridge Companion to Narrative, Cambridge:Cambridge University Press, σσ:61-79

- Μεταξάς Α.-Ι.Δ(1997), Προεισαγωγικά για τον πολιτικό λόγο. Δεκατέσσερα μαθήματα για το στυλ, Αθήνα:Σάκκουλας

- Μεταξάς Α.-Ι.Δ(2003), Η υφαρπαγή των μορφών. Από την πολιτική ομιλία του κλασικισμού, Αθήνα:Καστανιώτης

- Σαρηγιάννης Γιώργος (2005), «Πολεοδομικός εκσυγχρονισμός σε ελληνικά πλαίσια. Από τα σχέδια πόλης στην εμπορευματοποίηση της μεγαλοαστικής κατοικίας», στο Αργυρώ Βατσάκη(επιμ.), Πρακτικά συνεδρίου: Ελευθέριος Βενιζέλος και Ελληνική πόλη. Πολεοδομικές πολιτικές και κοινωνικοπολιτικές ανακατατάξεις, Αθήνα: ΤΕΕ, σσ:201-222

- Σαρτώ Μισέλ ντε(2010), Επινοώντας την καθημερινή πρακτική, Αθήνα:Σμίλη.

- Σταυρίδης Σταύρος(1999), «Προς μια ανθρωπολογία του κατωφλιού», Ουτοπία,τχ.33, σσ:107-121

- Σταυρίδης Σταύρος(2007), «Εικόνα και εμπειρία της πόλης στον Βάλτερ Μπένγιαμιν», στο Αγγελική Σπυροπούλου(επιμ.),Βάλτερ Μπένγιαμιν. Εικόνες και μύθοι της νεωτερικότητας, Αθήνα:Αλεξάνδρεια, σσ:250-272

- Σταυρίδης Σταύρος(2010), Οι μετέωροι χώροι της ετερότητας, Αθήνα:Αλεξάνδρεια

- Τερζάκης Άγγελος (2006), Μενεξεδένια πολιτεία, Αθήνα:Εστία

- Τουρνικίωτης Παναγιώτης(2000), «Ο δρόμος λέει τη δική μας ιστορία», στο Νίκος Βατόπουλος(επιμ.), Λεωφόρος Βασιλίσσης Σοφίας, Επτά Μέρες, εφ.Η Καθημερινή,5 Νοεμβρίου 2000,σσ: 22-26

- Φιλιππίδης Δημήτρης(2000), «Η αίγλη ενός αντιφατικού μύθου», στο Νίκος Βατόπουλος(επιμ.), Λεωφόρος Βασιλίσσης Σοφίας, Επτά Μέρες, εφ.Η Καθημερινή,5 Νοεμβρίου 2000,σσ: 16-21