Vertical social segregation in Athenian apartment buildings

Maloutas Thomas|Spyrellis Stavros Nikiforos

Built Environment, Ethnic Groups, Housing, Social Structure

2015 | Dec

Athens grew very dynamically in the first three post-war decades, during which its population more than doubled (from 1,500,000 in 1951 to 3,500,000 in 1981).

The city’s increasing population was housed in two main ways: a) individual privately-owned housing in the city’s outskirts, characterised by poor construction standards and b) housing in modern apartments built through the flats-for-land (antiparochi) system that mainly covered the needs of the middle and working-class social strata.

Flats-for-land, building density and social segregation

The flats-for-land system is a barter system based on an agreement between a land owner and a builder-contractor to construct a building and split the ownership of the apartments and/or offices and shops built, as per an initial contract describing each side’s level of participation in the relevant investment.

Its great success was due to:

- the huge demand for cheap and modern buildings by the city’s rising population and the expanding middle class, during the first post-war decades

- the fact that it was a system that suited small urban land property owners and construction businesses who lacked capital

- the policy of tax benefits that rendered it hard to compete with in terms of building construction costs

The apartment buildings of this kind, which are still the majority of the housing stock of Athens, were erected up to the late 1970s, to a large extent. Between 1950 and 1980, approximately 35,000 buildings with five or more storeys were built, while prior to this period the total number built did not exceed 1,000 buildings. After 1980, construction activity decreased significantly, particularly in the city centre.

The additions to and reshaping of the housing stock caused by the flats-for-land system through the rapid proliferation of apartment buildings had significant impacts on the city’s social geography (meaning, the way social groups are distributed within it). The two main impacts are related to:

- the redistribution of social groups throughout the metropolitan area

- the change of the social profile of central city areas, where the flats-for-land system was mainly applied

In relation to the first aspect, the flats-for-land system caused multiple chain reactions:

- rapid increase in building density, initially in central areas and then in areas around the city centre: during the period from 1951 to 1971, the resident population of the Municipality of Athens increased by more than 60% (from 550,000 to 890,000)

- deterioration of environmental conditions in the city centre, as the increase in density was not accompanied by improvements in infrastructure, while the situation was significantly aggravated by the large increase in the number of vehicles

The degradation of environmental conditions in central areas led to the gradual outmigration of a significant proportion of the middle and upper-middle strata to the north-eastern and southern suburbs. The upper social strata in particular showed significant spatial re-distribution: Between 1971 and 1991, the distribution in the upscale suburbs of upper social categories (public and private sector executives, freelancers and other professionals) increased from 10% to 30% and decreased in the centre (Municipality of Athens) from 62% to 27%. On the contrary, relocations were much more limited for employees (table 1).

Table 1: Spatial relocation of upper social and professional categories and salried workers depending on the social character of the areas of residence in the Athenian metropolis

Whereas higher building density degraded living conditions in the city centre, apartment blocks gradually became a “plebeian” version of the interwar urban apartment buildings in terms of building quality and lack of architectural imagination.

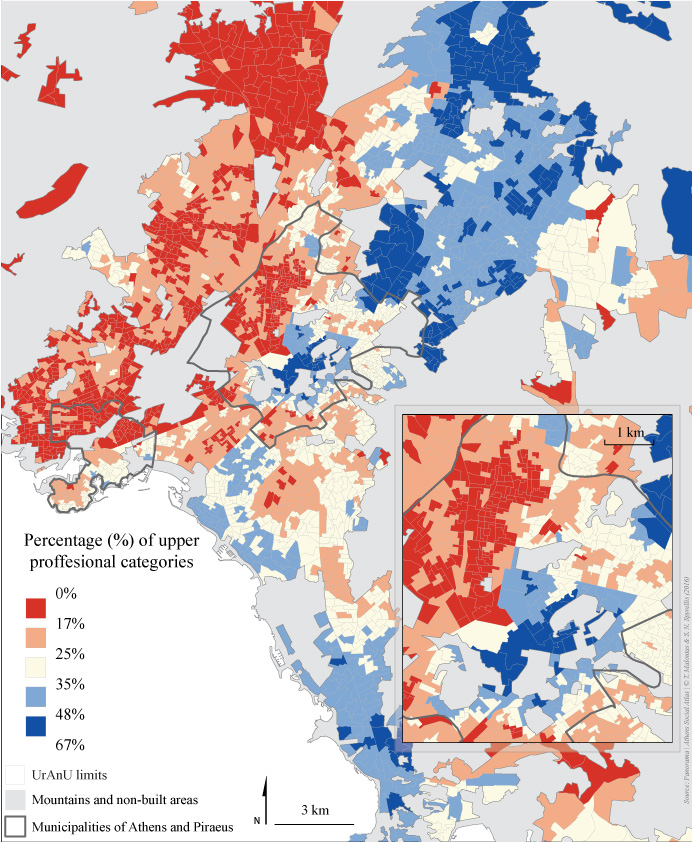

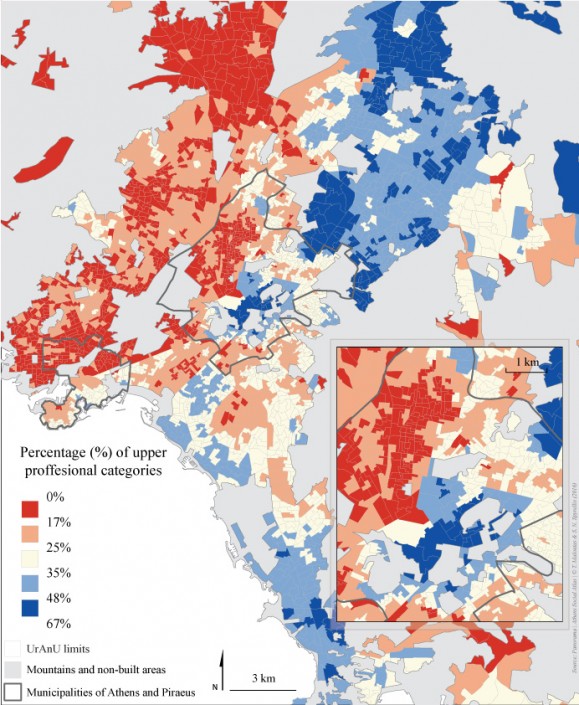

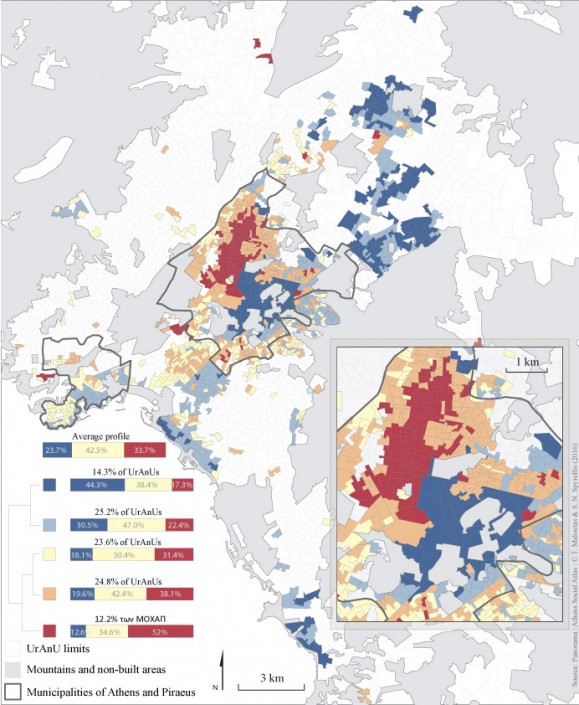

Due to these shifts, the East/West and not the Centre/Periphery division, became the dominant spatial expression of social separation of the part of the city that lies within the Attica basin. Athens, a city where upper social classes traditionally lived in the centre and working classes lived in the periphery, came closer to the paradigm of the English-speaking world, where the affluent live in the suburbs and the working class live around the centre. Lower social classes –other than their increased presence in the centre– still prevailed in most of the western suburbs and the more peripheral locations within Attica (map 1).

Map 1: Social differentiation of residential areas in Athens according to the percentage of upper professional categories (2011)

Vertical social segregation

The second aspect of the impact of the flats-for-land system were the changes that it brought about in the city core, namely:

- the significant population growth during the period when the flats-for-land system (1960-1980) was most extensively used to add dwellings to the housing stock, but also a decrease ever since (from 890,000 in 1981 to 660,000 in 2011), due to the degraded living conditions in the centre, caused by its uncontrolled development.

- the greater social mix, through the entry of lower-middle strata families in the growth period and the exit of upper-middle strata in the period of decline.

- the significant presence of migrant groups from the 1990s onward, who were attracted by the affordable living cost in declining city centre areas.

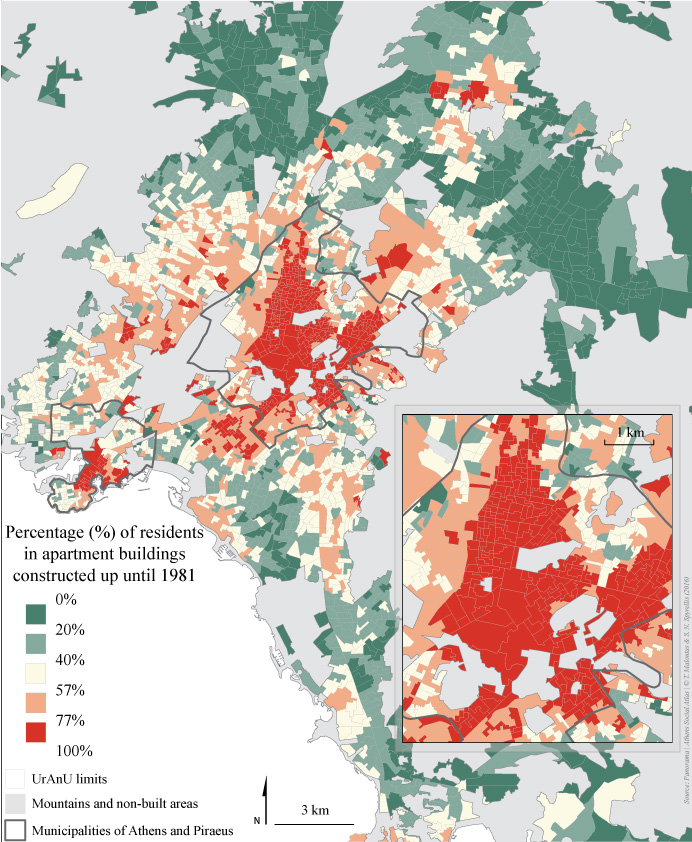

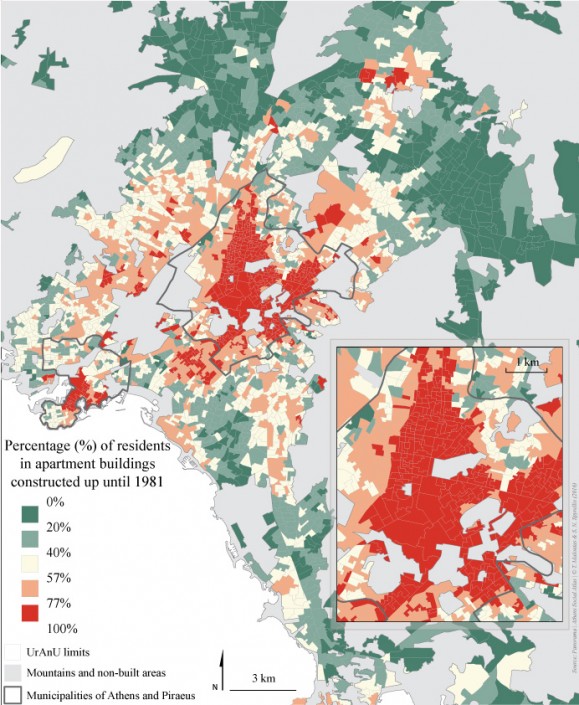

Map 2: Areas of Athens with most apartment buildings constructed up until 1981 (2011)

Sociospatial rearrangements were largely shaped by the structure of the flat-for-land apartment block per se, which allows for living conditions in the city centre to differ by floor: building density did not affect the upper and lower apartment blocks floors equally, contributing to create vertical social segregation.

Vertical segregation is largely due to the better conditions in the upper floor apartments (better view, less noise, more light, better ventilation, usable balconies…). In addition, upper floor apartments are usually larger (Figure 1). The difference in living conditions quality among different floors of the same building weighed more heavily for residents as building density increased

Figure 1: Percentage of residences by size and by floor, in apartment buildings in the Municipality of Athens (2011)

Figure 2: Percentage of professional categories by floor in apartment buildings in the Municipality of Athens (2011)

Figure 3: Percentage of individuals according to their level of education by floor in apartment buildings in the Municipality of Athens (2011)

Figure 4: Percentage of individuals by housing surface per head and by floor, in the Municipality of Athens (2011)

Vertical separation was identified and discussed many years ago (Leontidou 1990, Maloutas & Karadimitriou, 2001). However, while up until now, it was documented based on small scale field surveys, the 2011 Population Census offers the possibility to fully document it, as it is the first time that the floor of a building can be linked to resident characteristics. Thus, based on the 2011 census data, there is clear differentiation of social characteristics by floor in apartment buildings in the Municipality of Athens (Figures 2-6).

Figure 5: Percentage of individuals according to their nationality by floor in apartment buildings in the Municipality of Athens (2011)

Figure 6: Percentage of individuals by tenure and by floor in apartment buildings in the Municipality of Athens (2011)

The city neighbourhoods where vertical separation is possible are those where a significant percentage of residents could occupy the “extreme” social positions of the buildings (basements/ground floors and upper floors respectively). We should note, however, that not all of the flats-for-land apartment blocks offer those prerequisites.

Only those constructed until 1980 have a structure and an internal design favouring vertical social segregation. In these buildings, one can find small and deprived apartments in sub-basements and ground floors, as opposed to the more privileged, larger apartments in upper floors. In buildings of this period, a significant percentage of residents (40%) is concentrated in the “extreme” positions, of which 16% is in the ground floor or lower (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Population by floor in relation to the period in which the apartment building was constructed (Municipality of Athens)

Following changes in the Building Regulation in the early 1980s, there was a radical change in the use of basements and ground floors (to storage, under-deck parking, commercial uses); moreover quality differentiations among floors –from the 1st floor and above– decreased. Thus, vertical social segregation is only facilitated in flats-for-land buildings built until 1980. However, these apartment blocks still house the majority of the people living in apartment buildings (75% in the Municipality of Athens).

The concentration of population in apartment blocks constructed between 1946 and 1980 aids significantly in mapping vertical social segregation. Map 2 shows that the apartment blocks from this period are to be found primarily in some neighbourhoods in the Municipality of Athens (Patissia, Acharnon, Kypseli, Gyzi, Ampelokipoi, Pagkrati, Exarheia, Historical Centre, Kolonaki, Ilissia, Neos Kosmos) and secondarily in neighbourhoods in adjacent municipalities (Zografou, Kallithea, Nea Smyrni) and in the centre of Piraeus.

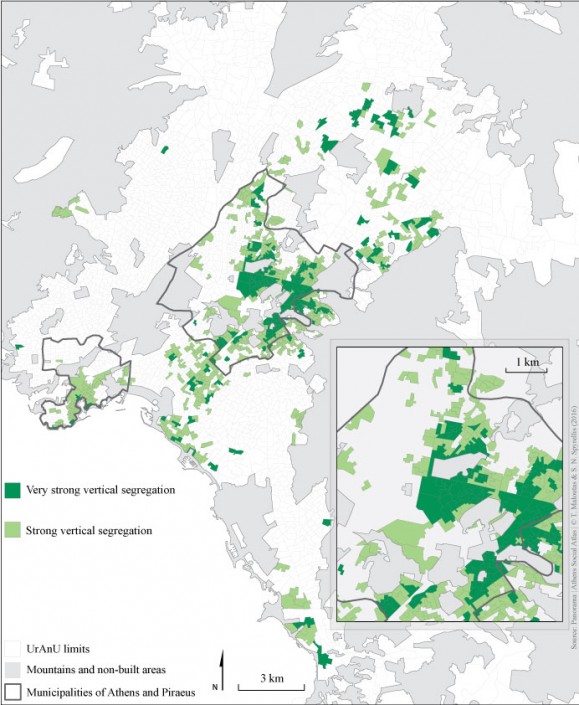

Mapping vertical social segregation

The detailed data of the 2011 Population Census (EKKE-ELSTAT, 2015) allowed us not only to certify the existence of vertical social segregation in Athens, but also to confirm that it concerns a significant percentage of residents, especially in the city centre. This data allowed for a detailed mapping at the level of Urban Analysis Units [URANU]. These units have an average population of 1,250 residents and constitute a re-processed form of Census Tracts used by the Hellenic Statistical Authority (ELSTAT) in order to avoid very small units (minimum population of URANUs: 900 residents).

Mapping vertical segregation presents significant challenges. In contrast to the conventional form of housing segregation (through which the social characteristics of units like municipalities or neighbourhoods are revealed), vertical segregation has not been mapped on a city scale until now. The main challenge in this case is to investigate how segregation can be recorded, when different social or ethnic groups literally live one on top of the other and not in different neighbourhoods. Using the standard mapping methods for social segregation, vertical differentiation cannot be highlighted and what comes out instead is the impression that the vertically segregated areas are simply areas of a more or less intense social or ethnic mix.

Given our intention to shed light on the pattern of vertical social segregation in the clearest possible way, we focused on the population concerned by this phenomenon, i.e. the residents of apartment buildings constructed between 1946 and 1980. It is a significant part of the population, reaching 70% for the Municipality of Athens. In addition, we limited our mapping to URANUs with a population of at least 150 individuals where those who lived in “extreme” building positions (basements and ground floors as well as 4th floor and above ) represented at least 15% of the population. Thus, we selected 1,010 URANUs –from a total of 3,000– for the entire metropolitan area. 426 of those URANUs are located in the Municipality of Athens and the remaining belong to neighbouring municipalities –such as Kalithea– or certain suburbs that were planned under a special status –such as Cholargos and Palaio Faliro– as well as in the second largest centre, the Municipality of Piraeus.

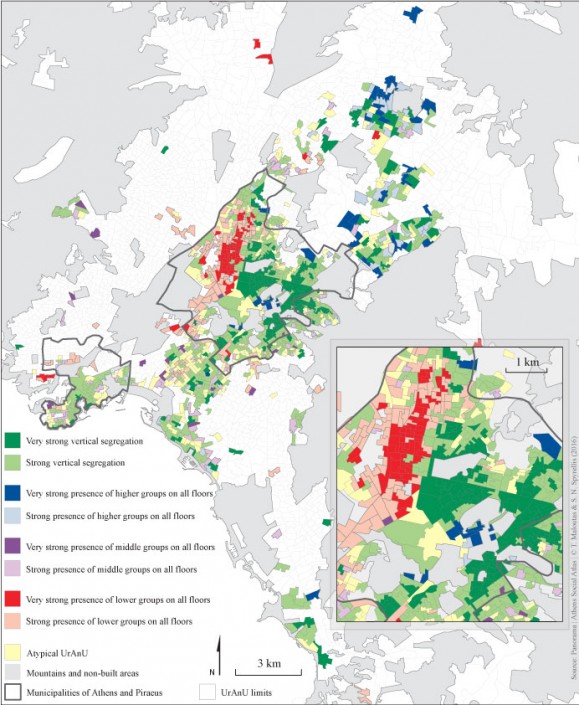

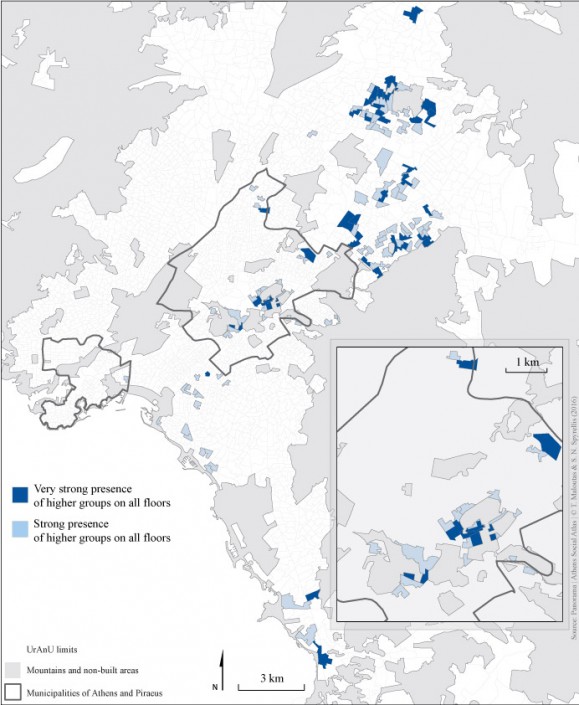

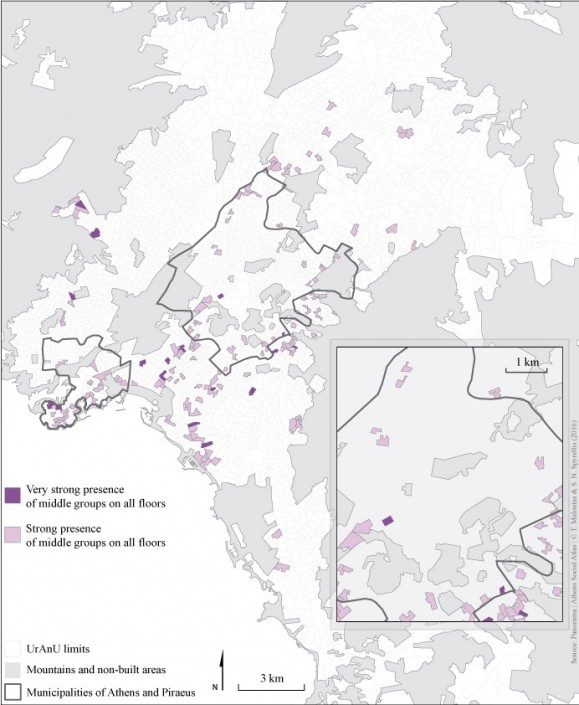

The key task was to map areas of vertical segregation and differentiate them from areas where no such phenomenon exists. The main assumption was that in the vertical segregation areas, higher social categories and/or the dominant ethnic groups would be over-represented in upper floors and lower categories and vulnerable groups would be over-represented in ground floors and basements. .

In practice, and to simplify things, we grouped floors in three categories: low=ground floor and basement, middle=1st to 3rd floor and high=4th floor and above. In a similar way, we grouped social categories as follows: upper=managers and professionals, intermediate=technicians, office staff and freelancers and lower=skilled and unskilled workers. We defined two levels of over-representation of social or ethnic categories: intense over-representation when the percentage of the category is larger than its average in the metropolitan area by at least one s.d. (standard deviation) and simple over-representation when it exceeds the average up to one standard deviation.

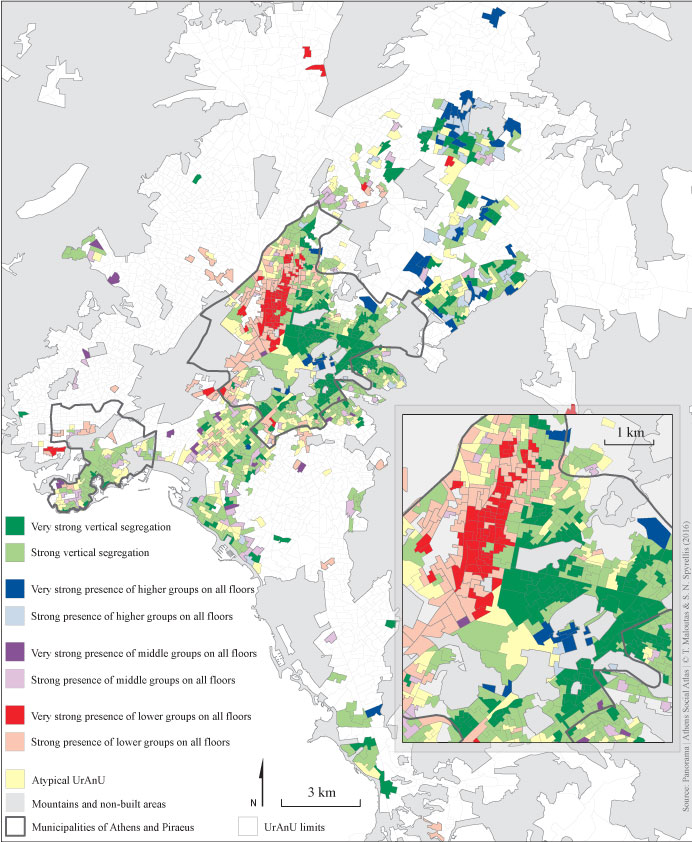

In the map of vertical social segregation (Map 3), the areas have been initially differentiated between socially homogeneous and vertically segregated. Socially homogenous areas include those URANUs where one of the three basic social categories is intensely or simply over-represented in all floors. Vertically segregated areas include all URANUs where upper categories are over-represented in upper floors and lower categories are over-represented in lower floors. Intense over-representation is mapped with darker colours . Map 3 shows that the highest percentage of the 1,010 URANUs included in the analysis concerns areas of vertical social segregation (marked with dark green for intense and light green for simple over-representation) and that the phenomenon is particularly intense in areas such as Gyzi, Exarchia, Neapolis, Kypseli, Ampelokipi, Zografou etc. Socially homogenous areas across floors are fewer, particularly when referring to high social categories (marked in blue) and, mostly, intermediate ones (in purple). However, there is a significant and spatially-consistent concentration of low categories (in red) in the wider area around Patission and Acharnon avenues.

Map 3: Vertical social segregation and socially homogeneous areas in Athens (2011)

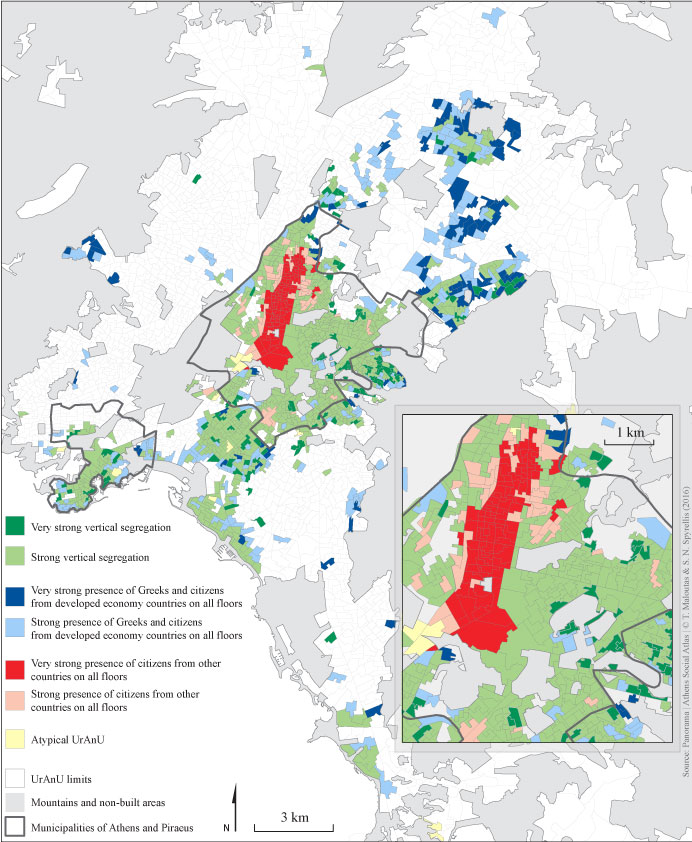

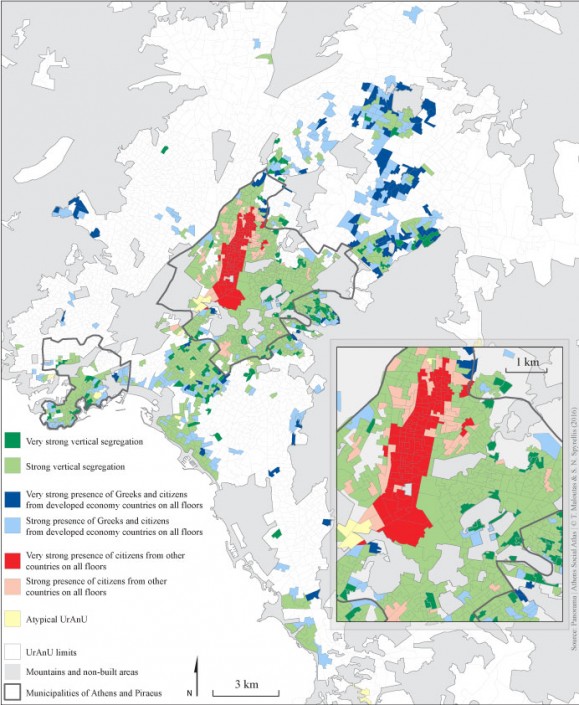

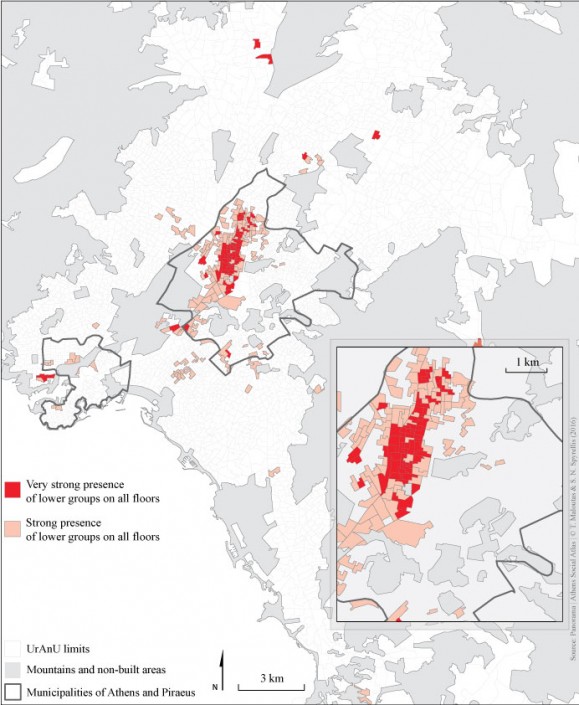

Map 4 illustrates vertical ethnic segregation referring to the over-representation of migrants on lower floors depicted in figure 5. Notwithstanding the differences between the two maps, their similarities leave no doubt about the strong correlation between social inequality, ethnicity and floor of habitation, especially in central regions.

Map 4: Vertical social segregation and ethnically homogeneous areas in Athens (2011) (residents of buildings constructed between 1946 and1980)

Conclusion

Vertical social segregation in areas with flats-for-land apartment buildings in Athens illustrates how the built environment can reflect the city’s social geography, with dynamics that are usually neither planned nor predictable.

Vertical social segregation is not an exclusive characteristic of Athens. It appears in the 19th and early 20th century in Paris and other cities of continental Europe with a different logic and a reverse social direction: affluent individuals lived in the lower floors and poorer in roof apartments. At the time, this form of segregation could be found in buildings without a lift that mainly housed the middle and upper-middle class. The traces of this form of vertical segregation have been erased as upper floors were upgraded (full renovations, connection of small apartments, addition of lifts) and the social character of their tenants has changed either through displacement (gentrification) or through gradual expansion of the upper-middle class (embourgeoisement) in neighbouring areas.

This specific form of vertical segregation in Athens and, above all, its importance are specific to the city. This characteristic sets Athens apart from other major Greek cities (with the exception of Thessaloniki to an extent) mainly because the flats-for-land system in other Greek cities developed later and, as a result, the percentage of buildings constructed prior to 1980 was smaller.

The negative aspects of the flats-for-land system in terms of the city’s urban planning are known and have been discussed in detail. The positive aspect is that it created social co-habitation areas through vertical segregation. However, the experience of the 1990s with the important migrant inflow has proven that social and ethnic mix do not guarantee an harmonious co-habitation nor a convergence of lifestyles among different groups residing in the same spaces.

The large building stock created by the flats-for-land system is located in city areas with many social problems, which have been aggravated during the crisis. Those areas have a significant percentage of empty apartments and vacant business premises, due to limited market demand and lack of maintenance of the building stock, while at the same time there are groups with significant housing needs (the unemployed, migrants, senior citizens). This leads to a stressful situation on the housing market for both tenants and for small-scale owners. Taking into account these difficult circumstances, which have been worsened by the taxation of small-scale property, these problematic areas could offer some advantages for the development of social housing policies based on matching unused resources and unsatisfied needs, and on the strengthening of relations of mutual help among local groups.

Entry citation

Maloutas, T., Spyrellis, S. (2015) Vertical social segregation in Athenian apartment buildings, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/vertical-segregation/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.14

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

References

- Αντωνοπούλου Σ (1991) Ο μεταπολεμικός μετασχηματισμός της ελληνικής οικονομίας και το οικιστικό φαινόμενο 1950-1980. 1η έκδ. Αθήνα: Παπαζήσης.

- ΕΛΣΤΑΤ – ΕΚΚΕ (2015) Πανόραμα Απογραφικών Δεδομένων 1991-2011. Available from: https://panorama.statistics.gr/.

- Πρεβελάκης ΓΣ (2001) Επιστροφή στην Αθήνα. Πολεοδομία και γεωπολιτική της ελληνικής πρωτεύουσας. 1η έκδ. Γκανά Π (επιμ.), Αθήνα: Εστία.

- Leontidou L (1990) The Mediterranean city in transition: Social change and urban development. 1st ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Maloutas T, Arapoglou V, Kandylis G, et al. (2012) Social polarization and de-segregation in Athens. 1st ed. In: Maloutas T and Fujita K (eds), Residential Segregation in Comparative Perspective. Making Sense of Contextual Diversity, Farnham: Ashgate, pp. 257–283.

- Maloutas T and Karadimitriou N (2001) Vertical social differentiation in Athens: alternative or complement to community segregation? International journal of urban and regional research 25(4): 699–716. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17672030.