Social housing estates in Athens

Myofa Nikolina

Built Environment, History, Housing, Planning, Politics, Quartiers

2021 | May

The most common form of public housing provision in Greece, and specifically in the Athens, was the construction of social housing estates, as was the case in the rest of Europe. These estates were designed by public agencies mainly from the interwar period to 2004. This study aims to indicate the context within which social housing in Athens was developed, its evolution and the analysis of the causes that led to its decline. Thus, through the study of the Athenian case, in the context of being an ineffective model of housing provision, the main research question of this paper, regarding housing estates, is: What are the current challenges the housing estates are facing? [1]

Social housing policy in Athens

In Greece, there was no official definition of social housing (Dimitrakopoulos, 2003).

The concept of social housing has historically been shaped in Greece according to the needs and purposes it would serve as well as the beneficiaries (to whom these houses were provided). So, there was housing for the refugees, the popular class and the working class, respectively (op. cit.). In this paper, we use the more general term ‘social housing’, which includes all the previous types.

The type of social housing in Greece has always been residual. It targeted specific groups of the population (refugees, internal migrants, salaried workers and residents who lived at old estates in inadequate housing conditions) who were not property owners and was directly associated with slum clearing programmes (part of them) and construction of social housing estates. Also, the apartments were given to beneficiaries for homeownership, not for rent (Kandylis et al. 2018). In fact, Greece remains the only European country whose housing model is characterized by the complete absence of the social rental sector (Pittini and Laino, 2011). Therefore, the Greek social housing policy was and continues to be aimed at urgent temporal needs, for example, the housing of victims of wars, natural disasters and earthquakes (Kandylis et al., 2018).

The historical review of social housing development in Athens concerns the following four periods: 1922–1939, 1950–1974 and 1975–2012. These periods are closely related to various events, such as huge population exchanges during 1920s, wars, migration flows etc., which changed Athens’ demographic and social profiles and usually induced important housing needs. These needs were urgent or less urgent as will demonstrated in the analysis that follows.

The interwar period (1922–1939)

The sector of social housing was developed for the first time after the Asia Minor Catastrophe and the need for housing large numbers of refugees from Asia Minor, Eastern Thrace and Pontus due to the defeat of the Greeks in the Asia Minor Campaign in 1922 and the subsequent signing of the Lausanne Treaty in 1923. The housing of a large number of refugees was difficult for the state to accomplish due to three factors: a) lack of previous experience in the field of housing rehabilitation, b) absence of public policy for the housing of vulnerable social groups and c) limited available financial resources. The reason was the two Balkan Wars and WWI that had preceded the Asia Minor Catastrophe (Γκιζελή, 1984).

During the 1920s, the Refugee Care Fund (TPP, in Greek, or Fund) and the Refugee Settlement Commission (EAP, in Greek, or Commission) were the two institutions that acted in the field of the refugee housing. The TPP was established by the Greek government, while the EAP was autonomous from the state but was supervised by an international organization, the League of Nations. More specifically, the TPP (began the construction of new settlements on the outskirts of Athens and Piraeus) was the first institution to that point which had dealt with the housing of vulnerable social groups, in particular, refugees. Hence, the Fund laid the foundation for the creation of a social housing sector after housing thousands of refugees (Γκιζελή, 1984). Also, the ΕAP continued the refugee housing work until 1930 (Λεοντίδου, 2001).

Despite the action of the public agencies some refugees who remained homeless settled on vacant land and formed makeshift accommodations (Leontidou, 1990). Particularly in the city of Athens, the refugees self-promoted their housing near the existing settlements that were built by the state or wherever they found vacant land (Παπαϊωάννου, 1975).

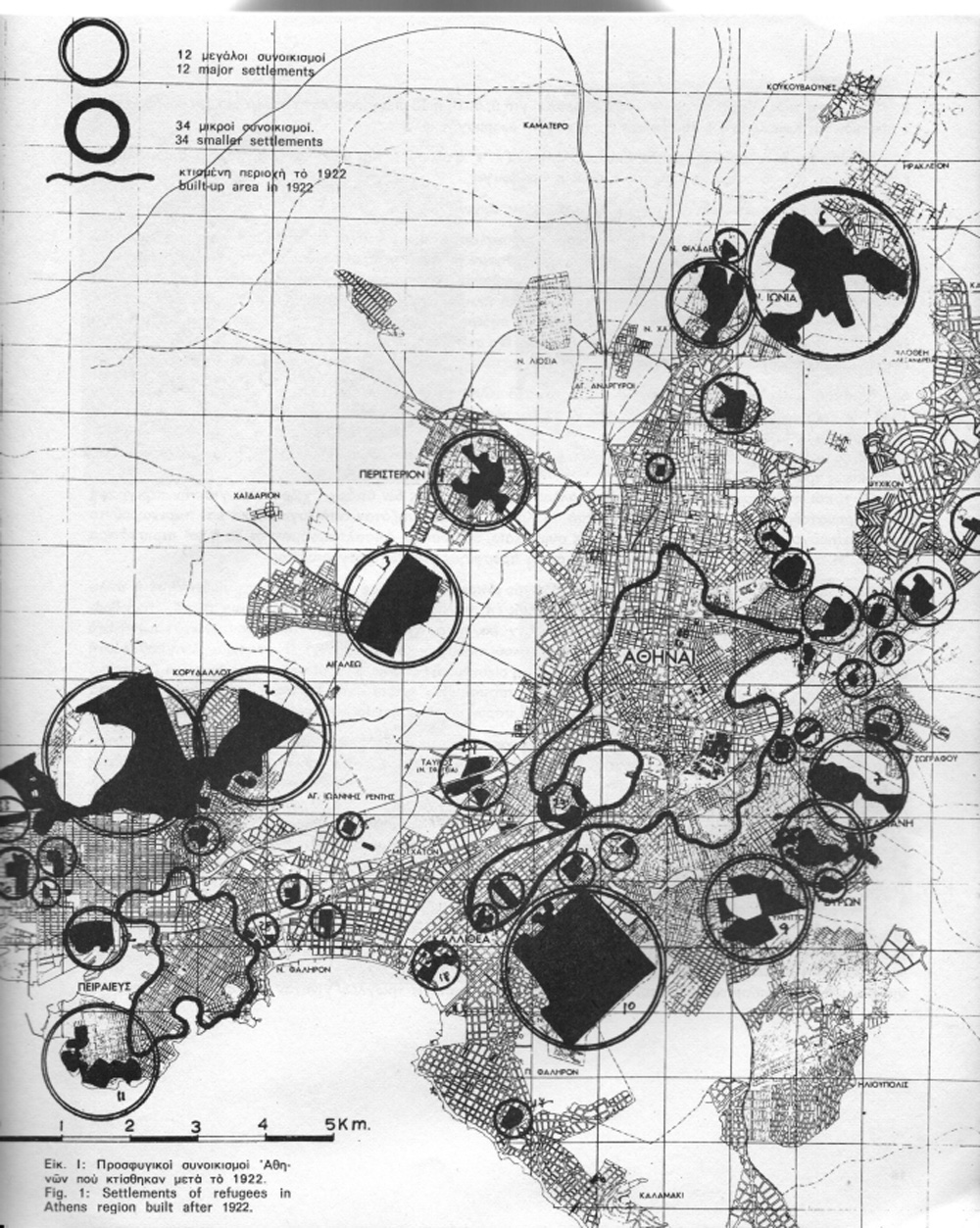

In total, for the refugee housing rehabilitation project during the interwar period, 12 principal and 34 secondary settlements were built outside the existing urban tissues of Athens and Piraeus. Eventually, this led to developing several suburban areas uninhabited before 1922 (map 1) (Παπαϊωάννου, 1975).

Map 1: Refugee settlements built after 1922 and until the end of the 1930s on the outskirts of Athens and Piraeus

Source: Παπαϊωάννου, 1975:15

The activity of the central government through the Ministry of Welfare began in parallel with the action of the two institutions. However, from 1930 onward, the Ministry continued as the only actor housing refugees (Leontidou, 2001). More specifically, during the decades of 1930 and 1940, the Ministry constructed housing estates in slum areas, after the demolition of the shacks, or near them (Vasiliou, 1944). The housing estates were influenced by the modern architecture of the time (Bauhaus School) (Kolonas, 2003). The beneficiaries of the apartments were the Asia Minor refugees who were the residents of the shacks. Four of the estates were located in Athens (Alexandras Avenue, Stegi Patridos, Erythros Stavros, Dourgouti and Kaisariani), one in Piraeus and the rest in the wider Piraeus region (Nea Kokkinia, Rentis and Drapetsona). They were built in two periods, 1933–1936 and 1936–1939, and were given to beneficiaries exclusively for owner-occupation and not for rent (Georgakopoulou, 2003, Vasiliou, 1944).

The allocation of the apartments was implemented through a lottery, taking into account the members of each family and provided that the beneficiaries’ families had no other real estate property of any sort (Σταυρίδης κ.ά., 2009). These apartment blocks constituted social housing estates, since they were constructed by the state for those who could not access housing on their own (i.e. refugees who lived in shacks). Beneficiaries were required to pay a low price to the Ministry – much lower than market price – in order to attain ownership of the apartment (Σταυρίδης κ.ά., 2009). The Ministry made it easier for them to pay the price by giving them the opportunity to repay 70% of the price that was spent on the purchase of the land and for the construction of the residence within 15 years (Βασιλείου, 1944).

The impact of the state’s action for the housing of refugees regarding the overall issue of social housing is undoubtable. The sector of social housing was developed for the first time in Greece due to the need for housing such a large number of refugees, and this laid the foundation for the creation of a wider social housing policy (Λυγίζος, 1974). Nevertheless, while the task of housing thousands of refugees was in progress, this was not the case for the poor social strata of the native population. Social housing was strictly understood as refugee housing (Γκιζελή, 1984).

Post-war period (1950–1974)

Housing needs after the Civil War, that followed WWII, were also significant. Moreover, in the 1950s, there were refugees for whom the problem of housing remained unresolved. The housing stock decreased due to war catastrophes, and the massive influx of internal migrants from rural areas into the cities (due to various reasons, such as civil war, job searching, etc.) intensified the housing shortage. During the post-war period, most social housing projects were undertaken by the Ministry of Welfare through slum clearance programmes and the construction of social housing estates. These estates were built to accommodate the Asia Minor refugees, as well as the natives who lived in shacks (Βασιλικιώτη, 1975α).

The beneficiaries of the apartments at social housing estates were low-income households who were settled in inadequate houses and were not homeowners or landowners in some other area. The allocation of the apartments was implemented, as in the previous period, by lottery. Again, the beneficiaries could not choose according to selected features (such as the number of the apartment’s floor, the dwelling size, etc.). Thus, the apartment they received was not guaranteed to satisfy their needs (op. cit.).

Also, the beneficiaries bought the apartment from the Ministry for a subsidized price. Therefore, due to the issue of the exchangeable properties (as I have already mentioned), the majority of the Asian Minor refugees and their descendants refused to pay the price for the apartment they were assigned (Σταυρίδης κ.ά., 2009). In contrast, the internal migrants paid for the apartments.

During the demolition of the shacks and the building of the new estate, beneficiaries were given a rent subsidy. In many cases, households were relocated from the neighbourhood they used to live in to another (Βασιλικιώτη, 1975α). These relocations, even though they resulted in better housing conditions, brought significant changes. These changes had to do with the aspects of everyday life amongst residents.

In that period, along with the Ministry of Welfare, the Workers’ Housing Organization (OEK in Greek) became active. The OEK was established in 1954 as an independent agency by the Ministry of Employment and Social Security. Until 1975, its revenue came primarily from employee contributions (Κοτζαμάνης και Μαλούτας, 1985). This organization provided housing for private-sector employees who were not homeowners. The OEK was the first organization that its housing policy meant to be a more comprehensive, mainly as opposed to the state policy which, until that point, gave priority to the housing rehabilitation of refugees, slum residents and other residents affected by various natural or anthropogenic disasters. However, the most vulnerable social groups – such as the homeless and the unemployed – were excluded from OEK’s social housing policy (Σαπουνάκης, 2013).

The beneficiaries were given either loans (for self-housing or buying a new house) or apartments in newly constructed housing estates. The OEK provided apartments to beneficiaries exclusively for owner-occupation and not for rent, just like the other public agencies that had provided social housing since 1922. The beneficiaries had to pay a low price to the OEK in order to purchase the apartment. The apartments were allocated by lottery amongst potential beneficiaries. In comparison with the Ministry’s similar process, the OEK lottery was based on social and localization criteria (Σταυρίδης κ.ά., 2009). For example, two of the main criteria were the distance from the neighbourhoods (without housing estates) and the proximity to potential employment areas (op. cit.).

The buildings constructed by the OEK were two-storey detached houses and three, four, eight and ten storey apartment buildings. In the design of the OEK housing estates, there was a provision for the formation of open spaces and green areas. The apartment buildings were arranged in rows with an appropriate distance between the buildings (to ensure adequate lighting and ventilation for the apartments) (Σταυρίδης κ.ά., 2009).

In conclusion, the Ministry of Welfare mainly dealt with emergencies that caused urgent housing needs, while the OEK programmes were geared towards specific population groups without direct needs but without taking into account the homeless (Leontidou, 1990). The number of dwellings that were constructed by the Ministry of Welfare and the OEK was small in comparison with other European countries. More specifically, the two agencies constructed 31 housing estates during the post-war period with approximately 11,930 dwellings, while, for example, in the suburbs of Stockholm, 34 housing estates with 83,796 dwellings were built from 1951 to 1970 (Andersson and Brama, 2018: 368).

From 1975 to 2012

Worldwide, after 1975, concerning the social housing policy, the tendency was to replace the social housing estate system with a new model. The new one provided financial assistance for the construction or the individual purchase of a house produced by private companies (Bourne, 1998). This change, as well as the decrease of the Ministry of Welfare programmes, also affected how policy was pursued in Greece (Βασιλικιώτη, 1975α).

The OEK was the main public agency that provided social housing from 1975 to 2011. Except for the construction of housing estates, OEK lent money to individuals in order for them to acquire housing and subsidized rent to beneficiaries that met specific criteria (Βαταβάλη και Σιατίτσα, 2011). The OEK’s activity in Athens, compared with that in the medium-sized Greek cities, was less important. Only 10% of the agency’s total activity from 1955 to 2012 was located in the metropolitan area of Athens (Kandylis et al., 2018). The OEK’s housing estates were primarily located in the north-western part of the suburban ring of Athens, in the north suburbs and in East Attica (op. cit.).

The Olympic Village was the last housing estate constructed by the OEK in Athens. This estate was constructed in order to temporarily house athletes during the Olympic and Paralympic Games held in Athens in 2004. After that, the dwellings were used for the housing rehabilitation of the OEK’s beneficiaries (Αραβαντινός, 2007).

The involvement of the last institution, the Public Enterprise of Town Planning and Housing (DEPOS in Greek), in social housing provision began during the same period. The DEPOS was founded in 1976 and was abolished in 2010. Its purpose was to provide affordable housing for the low- and middle-income social strata. The main activity of the DEPOS (supervised by the Ministry for the Environment, Physical Planning and Public Works) was the reconstruction of small-scale areas with old housing stock. These projects had to do with the renovation of the old housing estates that were constructed by the Ministry of Welfare during the interwar period at Nea Philadelphia, Kaisariani and Tavros (Νικολαϊδου, 1991).

The intervention of the state was necessary because these areas with the old post-war housing estates had deteriorated due to ageing, the abandonment of the old housing stock and to the inability of the residents to maintain and upgrade their individual apartments and, collectively, the entire estate.

In contrast to the other agencies, DEPOS’s action started at the request of the residents. The residents were involved in the process from the beginning of the redevelopment projects. These projects were implemented in cooperation with the municipalities, utilising democratic and participatory planning processes. In addition, until the project was completed, beneficiaries were given a rent subsidy (Στεφάνου κ.ά., 1995). DEPOS’s action was the exception to social housing policy that followed in the late 1970s, where the goal was no longer the provision of housing through the construction of apartment buildings. The intense reactions from private interests resulted in the reduction of DEPOS’s action from significant to insignificant activity until 2010 when it was abolished (Εμμανουήλ, 2006: 12).

Since 2012, when the function of the OEK was terminated, no public agencies for accommodating housing of low-income households have existed (Ζαμάνη και Γρηγοριάδης, 2013). The housing needs of vulnerable groups are therefore resolved through emergency/temporary solutions rather than by established housing policies.

General conclusions

In total, the three agencies − the Ministry of Welfare, OEK and DEPOS − from the interwar period until 2004 constructed 19,299 dwellings in the metropolitan area of Athens for the housing rehabilitation of three groups: 1) refugees and internal migrants who lived in shacks, 2) private-sector employees and 3) residents who lived in old social housing estates. Today, the share of people living in housing estates in the metropolitan area of Athens is very low, approximately 1.6 per cent, according to the 2011 census data (Kandylis et al., 2018). This proportion is low compare to 7.4% of the total population of Brussels which, according to 2011 census data, lives in social housing estates built during the period 1946-1990, 15.2% of the population of Stockholm that according to 2014 data lives in the 49 social housing estates and 19% of the total population of Helsinki that lives in the 48 estates (Hess et al., 2018).

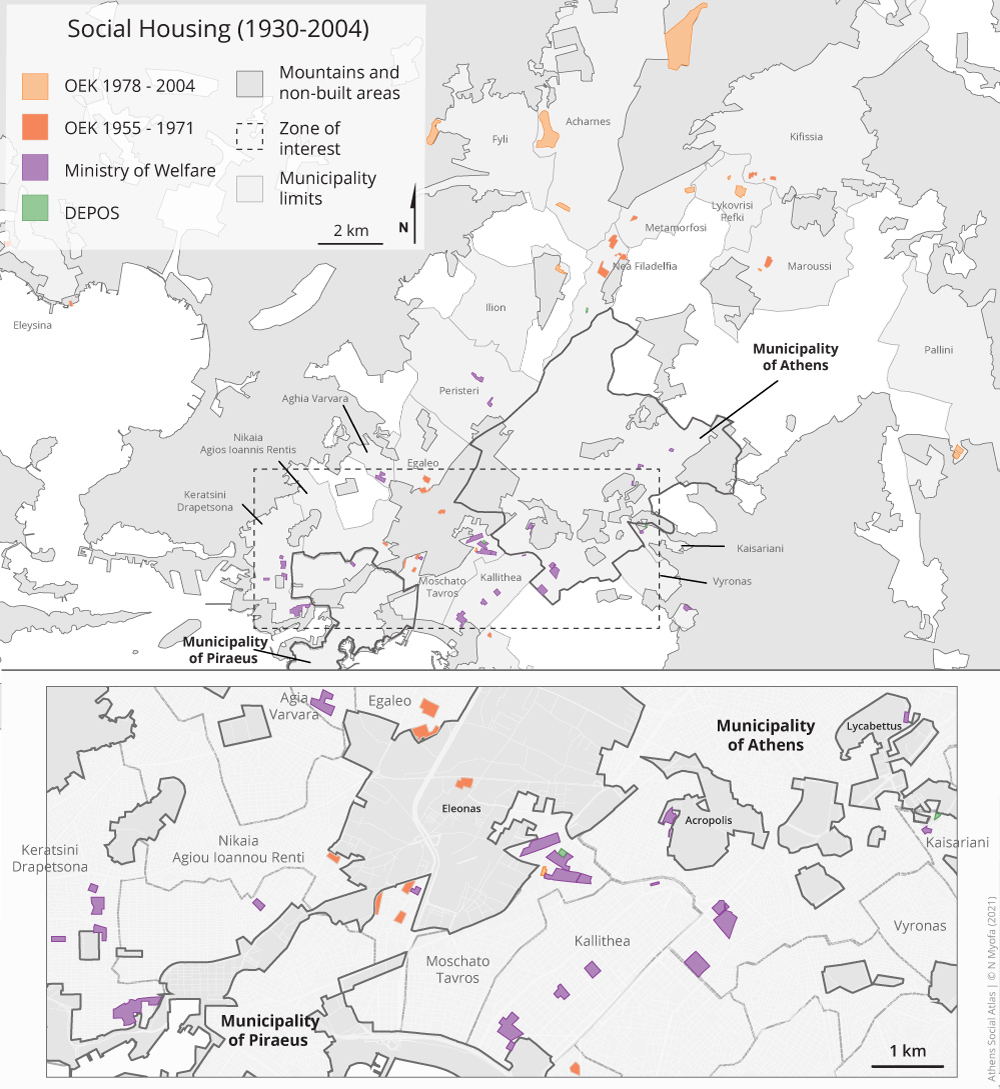

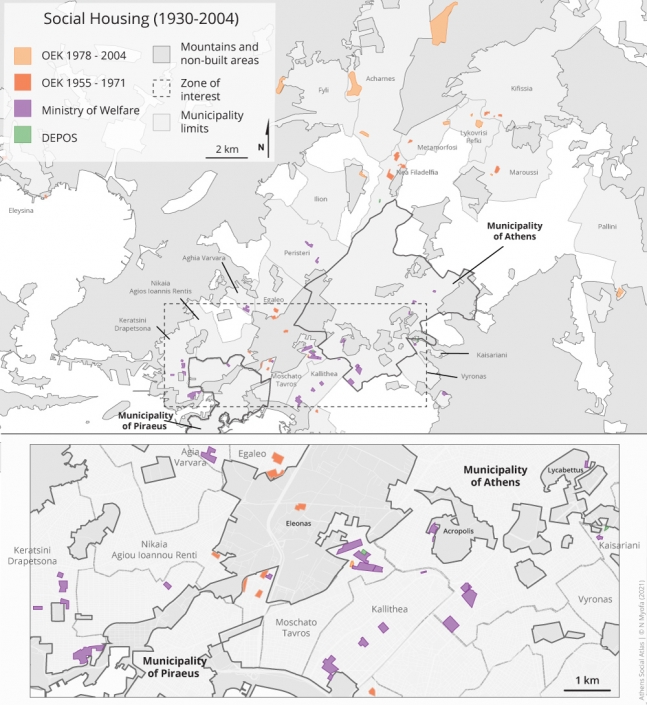

Map 2: Location of social housing estates constructed in the Athenian Metropolitan Area during the period 1930-2004

Data source: Βασιλικιώτη 1975β; Παπαδοπούλου και Σαρηγιάννης, 2006; Σταυρίδης κ.ά., 2009; Google Earth και τοπικές επισκέψεις.

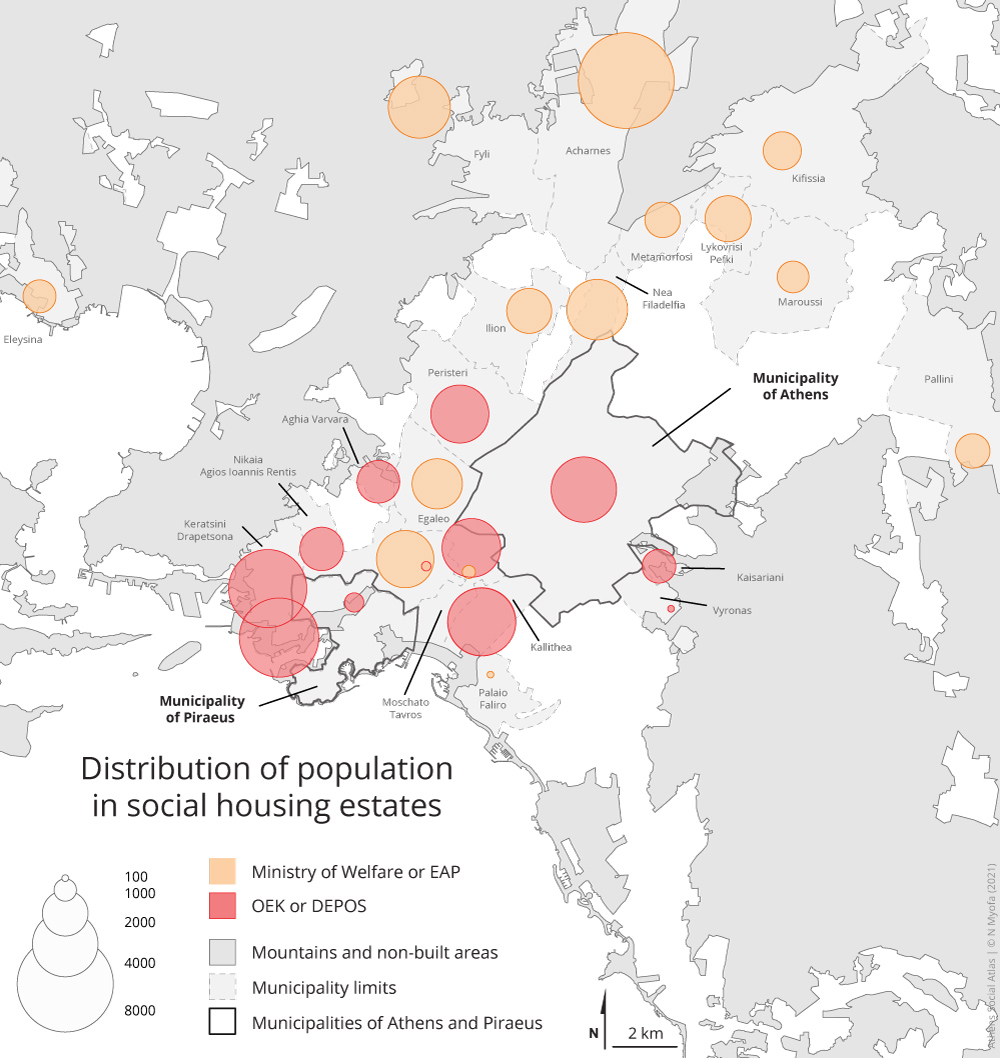

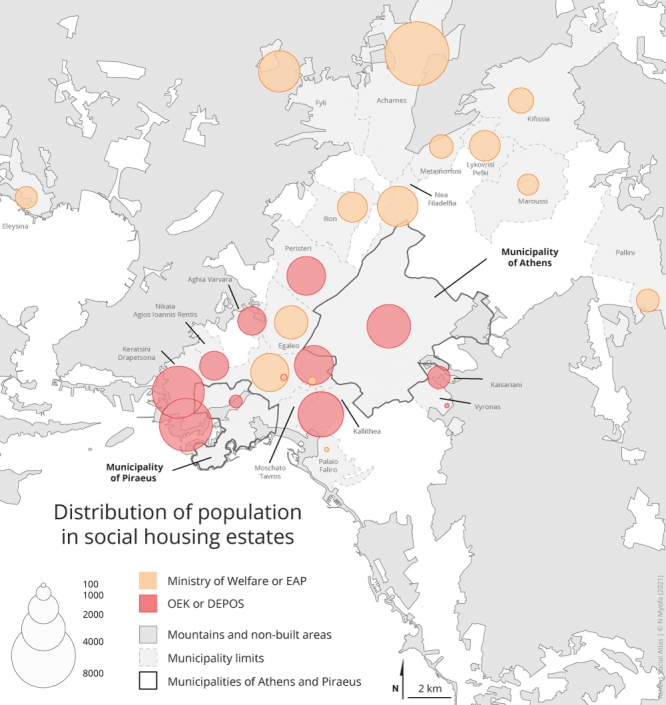

These estates are mostly in small areas with reduced populations. The following maps indicate the small area occupied in the housing estates that were constructed during the periods 1930–1974 and 1975–2004 (map 2). The number of residents in the Ministry of Welfare estates (yellow colour), and in the OEK’s or DEPOS’s estates (red colour) per municipality are represented with proportional symbols (map 3). Only four of these estates have over 3,000 residents, which are in peri-urban fringe (Olympiako Chorio and Acharnai) and in the western suburbs of working-class (Nea Filadelphia and Tavros) (Kandylis et al., 2018).

Map 3: Location of social housing estates constructed by OEK and DEPOS in the Athenian Metropolitan Area during the period 1930-2004

Data source: Βασιλικιώτη 1975β; Παπαδοπούλου και Σαρηγιάννης, 2006; Σταυρίδης κ.ά., 2009; Google Earth και τοπικές επισκέψεις.

The fact that the apartments in Greece were given for homeownership led initially to quite a homogeneous profile of the housing estates. Nevertheless, homogeneity started to change in the early 1990s with the inflow of low-income households from neighbouring countries attracted by the housing estates because of their low rents (Kandylis et al., 2018).

In addition, the fact that the apartments in these blocks were given to beneficiaries exclusively for owner-occupation and not for rent meant that this model of social housing, provided by the state, gradually lost its social character. The neighbourhoods in which these housing estates were located (in terms of their social characteristics and the housing market) would cease to be different from their wider areas once they followed the dominant housing model, that is, homeownership (Kandylis et al., 2018). Furthermore, as no social housing for rent was produced, the state immediately abandoned any responsibility for this housing stock. Instead, the owners were individually responsible for the maintenance and upgrading of their apartments and collectively for the entire estate, regardless of their financial situation. However, the financial inability of some of the owners led to the gradual degradation of the social housing estates. The abandonment of the apartments (especially in the estates that were constructed during the 1930s by the Ministry of Welfare) intensified this trend towards degradation. As a result, there is now a constant need for the redevelopment of the housing estates, although the public agencies that produced them have been abolished, and long before their abolishment, they were not responsible for their fate.

Even though these areas with housing estates have lost their social character and have gradually been integrated into their surrounding areas, they could still be reused through public intervention. The redevelopment of the apartment buildings could possibly lead to the resettlement of the residents (mainly those who have abandoned their apartments due to their degradation) in these areas. After all, both the redevelopment and the resettlement are a constant demand of the homeowners. Therefore, the reorganization of a public agency that could undertake the renovation of housing estates is of great importance. Also, the vacant apartments or those in limited use may be used as a form of social housing, with the consent of their owners, especially for those who are not able to find adequate housing using their own means.

[1] This paper is based on the literature review I have made in the context of my PhD thesis at Harokopio University. The thesis is entitled ‘Social housing in Athens. Study of the refugee settlements Dourgouti and Tavros from 1922 until today’. Part of this paper was presented at the Development Days 2020 Conference of the Finnish Society for Development Research ‘Inequality Revisited: In Search of Novel Perspectives on an Enduring Problem’, Helsinki: House of Science and Letters, 26–28 February 2020.

Entry citation

Myofa, N. (2021) Social housing estates in Athens, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/social-housing-estates-in-athens/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.101

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

References

- Αραβαντινός Α (2007) Πολεοδομικός Σχεδιασμός. Για μια βιώσιμη ανάπτυξη του αστικού χώρου. Αθήνα: Εκδόσεις Συμμετρία.

- Βασιλείου Ι (1944) Η λαϊκή κατοικία. Αθήνα: Π.Α.Διαλησμά

- Βασιλικιώτη Ε (1975) Μέρος II. Από το 1960 μέχρι σήμερα. Στο: Αμπαδογιάννη Β και Ζαβερδίνου Ο (επιμ.), Η κατοικία στην Ελλάδα. Κρατική δραστηριότης, Αθήνα: Τεχνικό Επιμελητήριο Ελλάδος, σσ 41–64.

- Βασιλικιώτη Ε (1975) Μέρος III. Συγροτήματα Αθηνών-Θεσσαλονίκης-Ρόδου. Στο: Η κατοικία στην Ελλάδα. Κρατική δραστηριότης, Αθήνα: Τεχνικό Επιμελητήριο Ελλάδας, σσ 65–146,

- Βαταβάλη Φ και Σιατίτσα Δ (2011) Η κρίση της κατοικίας και η ανάγκη για μια νέα στεγαστική πολιτική. Available from: https://encounterathens.files.wordpress.com/2011/05/politikes-gia-thn-katoikia-11mai11.pdf (ημερομηνία πρόσβασης 5 Φεβρουάριος 2015).

- Γεωργακοπούλου Φ (2003) Διερεύνηση της επιρροής του μοντέρνου κινήματος στον σχεδιασμό και την ανέγερση των προσφυγικών πολυκατοικιών στην Αθήνα και τον Πειραιά (1930-1940). Available from: http://bit.ly/ZFWxCQ (ημερομηνία πρόσβασης 15 Σεπτέμβριος 2015).

- Γκιζελή Β (1984) Κοινωνικοί μετασχηματισμοί και προέλευση της κοινωνικής κατοικίας στην Ελλάδα 1920-1930. Αθήνα: Επικαιρότητα.

- ΕΛΣΤΑΤ – ΕΚΚΕ (2019) Πανόραμα Απογραφικών Δεδομένων 1991-2011. Available from: https://panorama.statistics.gr/.

- Εμμανουήλ Δ (2006) Η κοινωνική πολιτική κατοικίας στην Ελλάδα: Οι διαστάσεις μιας απουσίας. Επιθεώρηση Κοινωνικών Ερευνών 120: 3–35.

- Κολώνας Β (2003) Η Αρχιτεκτονική στην Ελλάδα. Στο: Ιστορία της Ελλάδας του 20ού αιώνα: Ο μεσοπόλεμος 1922-1940., Αθήνα: Βιβλιόραμα, σσ 461–539.

- Κοτζαμάνης Β και Μαλούτας Θ (1985) Η κρατική παρέμβαση στον τομέα της εργατικής-λαϊκής κατοικίας. Επιθεώρηση Κοινωνικών Ερευνών 56: 129–154.

- Λεοντίδου Λ (2001) Πόλεις της σιωπής. Εργατικός εποικισμός της Αθήνας και του Πειραιά, 1909-1940. 2η Έκδοση. Αθήνα: Πολιτιστικό Τεχνολογικό Ίδρυμα ΕΤΒΑ.

- Λοΐζος Δ (1994) Οι μεγάλες δυνάμεις, η Μικρασιατική Καταστροφή και η εγκατάσταση των προσφύγων στην Ελλάδα (1920-1930). Αθήνα.

- Λυγίζος Γ (1974) Η λαϊκή στέγη στην Ελλάδα και στο εξωτερικό. Αθήνα: Τεχνικό Επιμελητήριο Ελλάδας.

- Νικολαΐδου Σ (1991) Η ανάπλαση ως μέσο άσκησης στεγαστικής πολιτικής στην Ελλάδα: κοινωνιολογική διερεύνηση των αποτελεσμάτων ορισμένων περιπτώσεων ανάπλασης. Επιθεώρηση Κοινωνικών Ερευνών 83: 77–99.

- Παπαδοπούλου Ε και Σαρηγιάννης Γ (2009) Η εγκατάσταση των προσφύγων του ΄22 στο Λεκανοπέδιο Αθηνών. Η σημερινή κατάσταση των προσφυγικών εγκαταστάσεων στην Αθήνα. Δυνατότητες προστασίας. Available from: http://www.monumenta.org/article.phpIssueID=2&lang=gr&CategoryID=3&ArticleID=8 (ημερομηνία πρόσβασης 17 Απρίλιος 2016).

- Παπαϊωάννου Ι (1975) Μέρος I, 1920-1960. Στο: Η κατοικία στην Ελλάδα. Κρατική δραστηριότης., Αθήνα: Τεχνικό Επιμελητήριο Ελλάδας, σσ 5–40.

- Σαπουνάκης Α (2013) Προβλήματα ένταξης σε κανονική κατοικία στην Ελλάδα τα οικονομικής κρίσης. Στο: Μανωλίδης Κ και Στυλίδης Ι (επιμ.), Μεταβολές και ανασημασιοδοτήσεις του χώρου στην Ελλάδα της κρίσης, Βόλος: Πρακτικά Συνεδρίου Τμήματος Αρχιτεκτόνων Μηχανικών του Πανεπιστημίου της Θεσσαλίας, 1-3 Νοεμβρίου 2013, Πανεπιστήμιο Θεσσαλίας, σσ 465–472.

- Σταυρίδης Σ, Κουτρολίκου Π, Βαταβάλη Φ, κ.ά. (2009) Μετασχηματισμοί της σχέσης δημόσιου-ιδιωτικού χώρου στα συγκροτήματα κοινωνικής κατοικίας των Ελληνικών αστικών κέντρων. Αθήνα: ΕΜΠ-Σχολή Αρχιτεκτόνων Μηχανικών, Πρόγραμμα Ενισχυτικής Βασικής Έρευνας.

- Στεφάνου Ι, Χατζοπούλου Α και Νικολαΐδου Σ (1995) Αστική ανάπλαση. Πολεοδομία, δίκαιο, κοινωνιολογία. Αθήνα: Τεχνικό Επιμελητήριο Ελλάδας.

- Andersson R and Brama A (2018) The Stockholm estates – A tale of the importance of initial conditions, macroeconomic dependencies, tenure and immigration. In: Hess D, Tammaru T, and Van Ham M (eds), Housing Estates in Europe: Poverty, Ethnic Segregation, and Policy Challenges, International Publishing: Springer, pp. 361–387.

- Bourne L (1998) Social Housing. In: The Encyclopedia of Housing, California: Sage Publications, pp. 548–549.

- Dimitrakopoulos I (2003) National analytical study on housing. RAXEN focal point for Greece. Athens: ANTIGONE-Information & Documentation Centre.

- Hess DB, Tammaru T and Van Ham M (2018) Lessons learned from a pan-European study of large housing estates: Origin, trajectories of change and future prospects. In: Housing Estates in Europe: Poverty, Ethnic Segregation, and Policy Challenges, International Publishing: Springer, pp. 3–31.

- Kandylis G, Maloutas T and Myofa N (2018) Exceptional social housing in a residual welfare state: Housing estates in Athens. In: Housing Estates in Europe: Poverty, Ethnic Segregation, and Policy Challenges, International Publishing: Springer, pp. 77–98.

- Pittini A and Laino E (2011) Housing Europe Review 2012: The nuts and bolts of European social housing systems. CECODHAS Housing Europe’s Observatory, Brussels. Available from: http://www.housingeurope.eu/file/38/download (accessed 14 May 2015).